“The Big Bang Never Happened”, by Eric J. Lerner, ISBN 978-0-679-74049-0, 466 pages (1992).

With a title & publication date like that, I supposed this would be a book which had attracted the attention of our late host. But when I checked with the invaluable “John Walker’s Reading List”, it had not made the grade. If Mr. Walker had reviewed it, I wonder if he would have been intrigued … or infuriated … or more likely both!

Lerner’s well-researched historical thesis is that people’s views of the universe are bound up with their views of their current societies. In difficult times, such as now, people gravitate towards a finite universe with a definite beginning & end; hence the attraction of the Big Bang. During expansive ages, people favor the concept of an ever-lasting universe which is infinite in both time & space. Mr. Lerner is just such an optimist.

Much of the book is an exploration of the ideas of Nobel-laureate Hannes Alfven, who studied electric currents in very low density plasmas. One of Lerner’s reasonable critiques is that cosmologists do not appreciate plasmas, while plasma physicists are not cosmologists. Lerner likens the efforts of cosmologists to explain the universe through gravity alone (e.g. Dark Matter) to the efforts of ancient astronomers to make an incorrect theory fit observations by introducing non-existent epicycles. Reality is that electromagnetic forces are incomparably stronger than gravity, by a factor of about 10^^43 (!). Lerner argues that very large-scale filamentary plasma currents can explain many features of the universe, such as the anomalous rotational curves of galaxies and the distribution of galaxies into cosmic-scale clusters and super-clusters, without the need to invoke an unobservable Dark Matter.

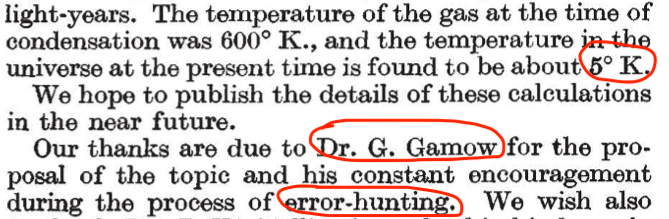

Two of the main observations used to support the “finite in time” Big Bang universe theory are (1) the highly uniform Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation, and (2) the distribution of light elements (hydrogen, helium, lithium) in the cosmos. Both observations can equally be explained through plasma physics. Lerner also reminds us that the original Big Bang prediction of the temperature of the CMB was about 10 times the measured value; then the prediction was adjusted.

Along the way, Lerner points out that a better appreciation of plasma physics could let us achieve nuclear fusion in a much safer & simpler fashion than the tokamaks on which so many decades and so much money has been expended.

Lerner later builds on the unconventional thermodynamic ideas of Nobel-laureate physicist Ilya Prigogine to contest the Big Bang idea that the Second Law of Thermodynamics condemns the universe to degrade into increasing chaos.

Despite his interesting takes on various topics, Lerner does seem to stroll around looking for toes to stand on. Some of those toes deserve to be stood upon, such as physicists who cling to failing theories, scientists who have become over-specialized, and academic peer reviewers who censors ideas that don’t fit with today’s conventional wisdom. But he also stamps on other toes which perhaps may not deserve that treatment, such as those of modern philosophers and theologians.

At the end of the day, is Lerner’s optimistic view that the universe is infinite in time & space (with no need for a Big Bang) convincing? I would say – No. But he makes a good case that our current cosmology may have backed itself into an epicycle-ridden dead end. There are other avenues which deserve to be properly explored, such as the effects of plasma physics at a cosmic scale.