The thing is, I don’t believe that. I didn’t believe it when I wrote The Hacker’s Diet in 1990, and I don’t believe it today, after more than three decades of experience managing my weight purely by calorie balance computed directly from a smoothed curve of daily weight measurements. Over that time, I have changed climates, made major changes in the things I eat and the schedule on which I eat them, changed the nature and extent of my physical activity, and medications (beta blockers) which affect basal metabolism, and I have observed nothing which indicates to me that anything other than the balance of the calories you consume and calories you burn matters, over the medium to long term, to whether one’s weight will go up, go down, or stay about the same.

If you weigh yourself every day, you’re looking at a small signal mixed with a very large amount of noise based on retention of water a numerous other factors. But simply filtering this signal with an exponentially smoothed moving average (the same technique radar sets use to plot the course of a target despite noise and jitter in return time) extracts a reliable trend line from the daily weights, and the slope of that trend line shows whether you’re gaining or losing weight and, from the chemical fact that the energy content of fat is around 3500 kilocalories (“food calories”) per pound, the size of your calorie excess or deficit. Fix your diet so you have a calorie deficit of around 500 calories a day, and you’ll lose around a pound a week for as long as you choose to remain on that diet. As far as weight loss or gain is concerned, it matters very little what you eat, although the choice of food and the schedule and regularity with which you consume it may make a great difference in how hungry you feel, how much energy you have, whether you’re subject to ups and downs or on a steady course, and your overall health.

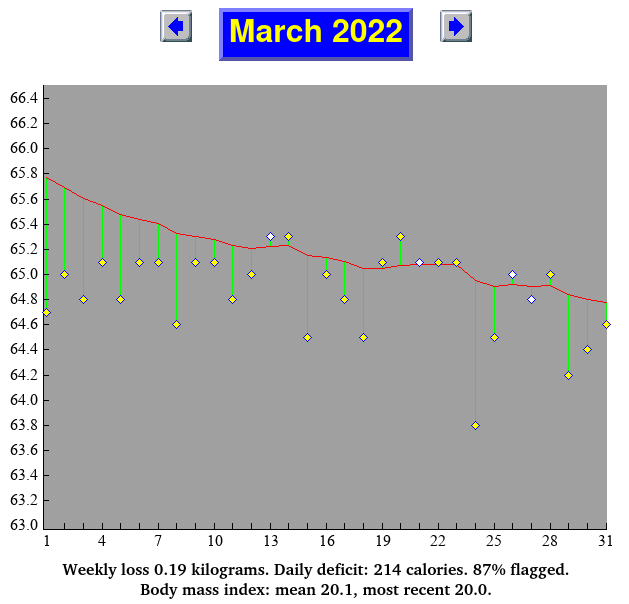

For example, below is the actual chart of my weight for March 2022, when I had decided to gradually bring my weight down from around 66 kilos to around 64.5. I decided on a gentle calorie reduction of around 200 calories per day, for a loss rate of around 200 grams a week. (I’ve found 500 calories per day easily tolerable when faster loss is required, but this was a smaller adjustment, so there was no reason to cut that much.)

The blue diamonds are daily weights, while the red line is the exponentially smoothed moving average of these weights (smoothing factor 0.1). The green lines just show the daily variance between the moving average and the smoothed trend. I call these “floats and sinkers”. A weight above the trend is a float that pulls it up, while one below is a sinker that pulls it down. As long as the weights are coming in below the trend, you’re losing weight, regardless of day-to-day variation in weight. As you can see, the daily weights were all over the place and could be an emotional roller coaster if you paid attention to them, but the smoothed trend was almost a straight line, and a linear regression fit to it shows a rate of weight loss and calorie deficit very close to the plan.

There’s an entire chapter in The Hacker’s Diet titled “Planning Meals” that discusses these details, how to plan around a calorie balance for a diet that’s enjoyable and healthy, and ways to avoid pitfalls that can torpedo a well thought out plan. But I don’t believe this has much, if anything, to do with whether you’ll gain or lose weight. In the end, thermodynamics always wins.

This has always worked for me, and it seems to work for lots of other people as well. Over the years since the first electronic edition on the Web in 1994, the book has been downloaded or read online more than 1.5 million times, and there are more than 34,000 accounts on The Hacker’s Diet Online service at my Web site. Both the book and online service have always been free.

I’ve never claimed this will work for everybody. In the conclusion of the book, I say,

If you want to recommend this book, hey, go right ahead. But just because this plan worked for you doesn’t mean it will work for everybody. Anybody can control their weight: it’s simply a matter of balancing calories, but the means that work for you may seem intolerable or utterly baffling to the next fellow. That individual may eventually become thin and healthy with a plan that strikes you as fascism cloaked in mumbo jumbo. In this book I’ve tried to present a relentlessly rational approach to weight control. You can’t persuade somebody to be rational. You’re better off trying to out-stubborn a cat.

Folks who’ve concluded “calories don’t count” should choose a different diet book, and diet book author.