The research paper, published in the 2022-10-03 issue of Ecology, is “Direct observation of killer whales predating on white sharks and evidence of a flight response”. Full text [PDF] is available at the link. Here is the abstract:

Killer whales (Orcinus orca) and white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) are marine apex predators which shape prey behaviour and even entire ecosystems, through direct predation effects and indirect fear effects ( e.g. Estes et al. 2009, Heithaus et al. 2008). Killer whales are known to occasionally hunt white sharks; although only three studies have formally described this behavior and the associated flight responses in white sharks (Pyle et al. 1999, Jorgensen et al. 2019, Towner et al. 2022a). However, direct observation of predation has been lacking, giving rise to speculation on the hunting strategies used by killer whales to capture and kill white sharks, and the subsequent behavioral impact on surviving white sharks in the area where the predation took place, including the cues and timing of shark responses to these events.

A popular article in ScienceAlert, 2022-10-05, “Watch A Great White Become an Orca’s Lunch in World-First Footage”, recounts the story.

In the harbor of Mossel Bay [South Africa] on the afternoon of 16 May [2022], a drifting drone caught sight of a white belly in the blue. A handful of killer whales were swimming near the surface, and the drone pilot – a hobbyist on the beach – decided to track them.

As the drone followed and recorded the group, a pair of orcas split eastward towards the local river’s mouth – a known hotspot for shark activity.

Two of the remaining cetaceans began swimming close together on the ocean’s surface, facing opposite directions, as though they were keeping a look out.

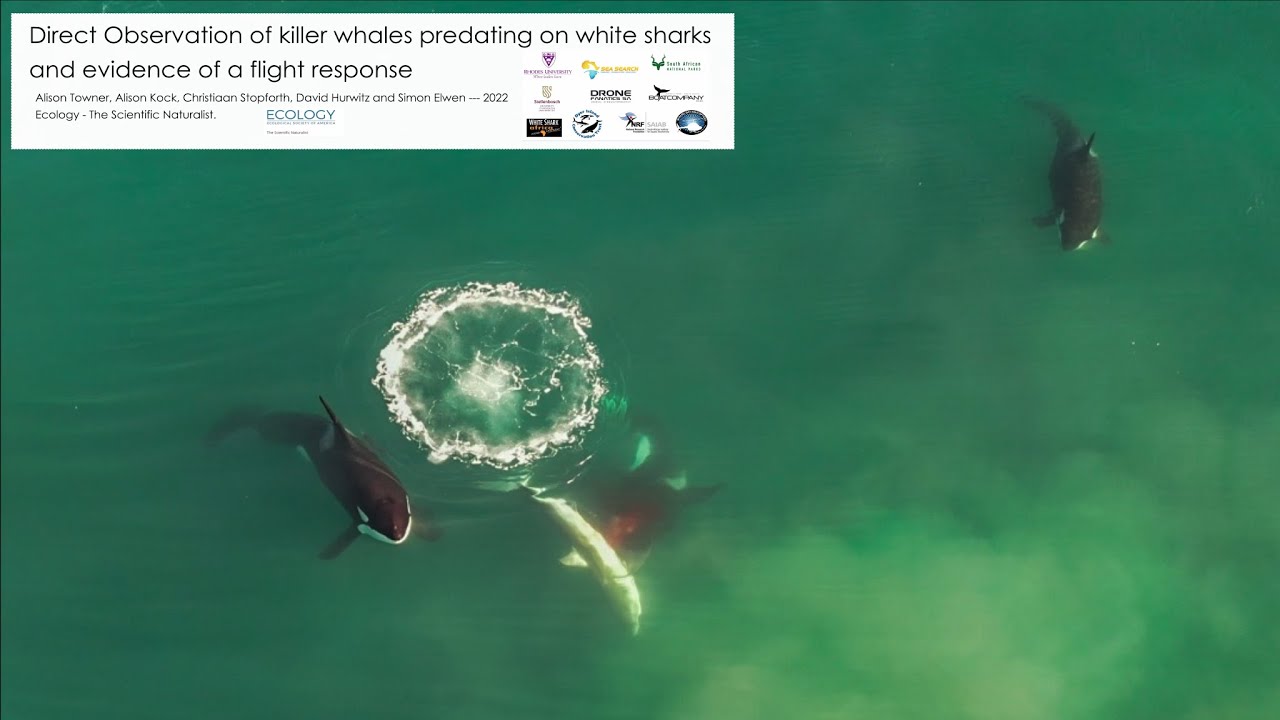

Seven seconds later, a fifth orca emerged from the deep right between the two patrols. Its nose was pushing a three-meter-long white shark, belly-side up, to the surface. With a quick flip, the orca rolled the shark on its side and bit into its belly behind its pectoral fin, blood spilling into the sea.

With the shark clasped firmly in the orca’s jaws, the fifth individual dove deep once more, releasing the carcass as it went.

One of the patrolling orcas then approached and grabbed the shark’s tail, pulling the once mighty hunter into the abyss, never to be seen again.

⋮

Four minutes before the feeding event, beach-based observers and the drone pilot reported seeing sharks fleeing the area. Some even came in to shore as shallow as two meters.

That day, ten sharks had been observed from the drone. But for weeks after the killing spree, hardly any sharks were seen in the area, based on satellite tags, drone surveys, and boat sightings.

The fact that Starboard, an older male orca, has now been caught hunting white sharks with a different pod of orcas suggests that the behavior may be spreading.

If more orcas adopt the practice, then it could have a serious impact on local shark populations, which are treasured and respected in Mossel Bay.

Fewer sightings of sharks off the coast have led some to blame illegal hunting activities and overfishing for their absence. But that might not be true after all.