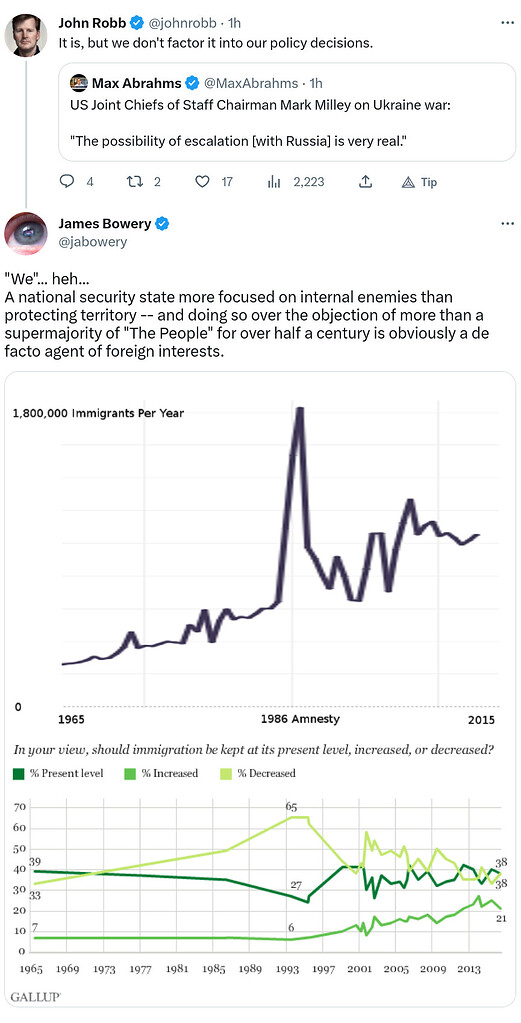

Andy says $15k would enable him to complete the editing of “Crowbar” and publish this year.

BTC: bc1qxn4fwu0j974xzgleczrv83u8u3dd0jq83vp5lf

PayPal: aslinged at yahoo dot com

Venmo: @goldengoatguild

Crowdfunding details:

via GoldenGoatGuild | Instagram, Facebook | Linktree

I didn’t realize Hillsdale College’s J. A. Jacson of had reviewed Edwards’s prior novel but here it is:

King of Dogs: Life is the Training Ground for Death

by Andrew Edwards, Golden Goat Guild, 2019

In his notebook to Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky writes, "Man is not born for happiness. Man earns his happiness, and always by suffering but for suffering.” Andrew Edwards’ King of Dogs is a long meditation on suffering, amongst other things, though it may not be as confident in man’s ultimate happiness as was Dostoevsky. It may also be even more hopeful. On a first reading, Andrew Edwards’ King of Dogs gives us a vision of America post-economic and political collapse. Paid militias run the cities for various oligarchs; there are turf wars, water wars, and other violent means towards ubiquitous commodification (including humans, children even). Edwards paints a bleak picture of the political world and, perhaps, an even bleaker one of the humans that inhabit it. His depictions of the natural landscape are vivid, and he does not flinch when it comes to depicting violence; indeed, his meditations on justice, mercy, revenge, and the afterlife dictate that these violent moments be represented as viscerally as possible. In many ways, one could see Edwards’ willingness to portray a sort of primordial violence, often in a quasi-detached manner, as a literary inheritor of Cormac McCarthy, but I think that would be slightly off-the-mark. He’s McCarthy in the inverse: whereas many critics must probe McCarthy’s works for a transcendental/metaphysical signified, Edwards’ is front-and-center for the reader, the very core of the novel. The McCarthy-like apocalypticism and brutality of the narrative can easily seduce the reader into thinking that that’s what the novel is about. Rather, I believe the metaphysical/religious narrative is aptly grounded in the apparent uselessness of pain and suffering in this world. Edwards’ playground is the metaphysical realm, and suffering, chaos, violence, and death are simply the backdrop. Where in McCarthy one has to squint to see a metaphysics, for Edwards, the metaphysical realm seems to be all that is permanent, graspable, certainly all that is rational. The rest of the world, and its incumbent suffering, comes off as simply irrational and temporary—brutal, often without remorse, but temporary nonetheless.

The novel’s protagonist, Grayson, finds himself duty-bound to his mentor’s family’s safety and must fight his way through a heavily militarized terrain, including even being hunted down himself (one of the most riveting scenes of the novel). He does so with honed survival skills, his wits, and his quiet prayer life. It’s the last of these qualities I’d like to focus on because it truly is the very heart of the novel. While the spiritual meditations aren’t woven seamlessly into the novel but appear as narrative or mental digressions, I find that these are the most challenging aspects of the novel. The novel clearly uses Eastern Orthodox spirituality as a backdrop; indeed, the novel makes clear that Grayson is a practicing Orthodox Christian. Edwards has created an interesting twist to his Orthodox spirituality that many readers may find hard to come to terms with: he takes Orthodox spiritual asceticism and applies it to a militarized, violent world; he takes the tenets of prayer life and makes that the very terms of earthly existence, with all the earthly shit that accompanies it. Colored with a sort of this-world stoicism and yet always keeping an eye towards a Christian telos, the novel should provoke manifold questions from its readers, Christian and non-Christian alike. I hesitate to call Grayson a hero, but he’s certainly no anti-hero. The reader will want to see him succeed but also flinch in watching him do so. The novel seems to stake out a simple position: the end of a political orderliness doesn’t make men vicious; the loss of law simply unveils the viciousness always already lurking. One wonders how enmeshed Grayson is in this world. He walks a fine line between violence and justice, it seems. However, he’s a problematic character only in so much as we’ve seen his thoughts, his commitment to prayer, to the Church, to Christ. Grayson seems both defeated and indefatigable—corrupted but untouchable.

In short, if this review can provide anything to its readers, it a simple piece of advice: do not skim the spiritual meditations. The suffering and violence of the novel are simply a difficult (too difficult?) vehicle through which the spiritual tenor is offered. I recommend this novel not to just those interested in shifting global-American politics/economics today (though it’s an invigorating read just for this aspect), nor to those who enjoy the “survivalist” genre (though some of its most memorable scenes follow this genre perfectly), but to those who wish to have their vision of this world and the next challenged. I question some of the application of Orthodox theology/spirituality espoused by the novel, but to question does not mean to dismiss. It’s a difficult spirituality because the novel is set in difficult times. The novel offers its readers a challenging ethical vision. But this leads me, finally, to the highest compliment I can give as a reviewer: once I finished the novel, I wanted to go back and read it again to see what I missed.

J. A. Jackson

Edrie Seward Kennedy Chair in English

Hillsdale College