Fixed-income securities such as bonds and shorter-term debt instruments such as Treasury notes and bills are a sucker bet in times of inflation because, over the term of the bond, the purchasing power of the money in which it is denominated and the interest it pays decreases, meaning when the principal is repaid, it is worth less than what you paid originally for the bond. In times of rising inflation, the interest payments will not usually make up for the loss in principal. So, not only have you lost the use of the money for the term of the investment, you’ve also lost purchasing power: lose-lose.

Consequently, investors are wary of bonds when inflation is on the horizon which, in the era of funny money backed only by the integrity and honesty of politicians ushered in by the destruction of the gold standard by the United States in 1971, it almost always is. To invite (or, it you like, sucker) investors into buying its debt, the U.S. Treasury created instruments called “Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities” (TIPS), in which the face value and interest payments on the bond are indexed to inflation by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), supposedly providing a shield from inflation by adjusting the pay-outs to compensate for erosion in the purchasing power of the money. (Of course, since the Consumer Price Index has been the subject of jiggery-pokery to understate inflation since the 1980s, this is also a scam, but we’ll set that aside for the moment.)

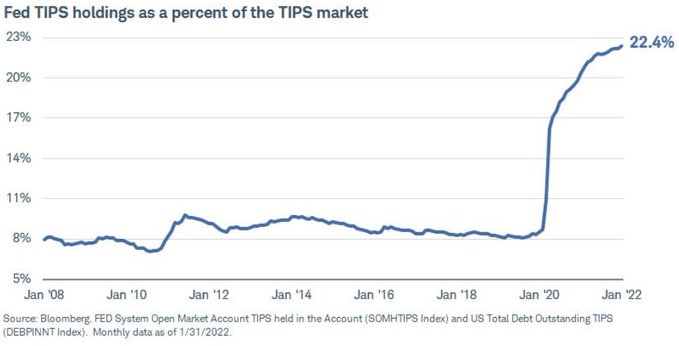

What is delightfully ironic is that when, starting in 2020, the U.S. Federal Reserve went on a wild bender of money printing through the instrument of buying U.S. Treasury securities with “dollars” made up out of thin air, they put a substantial part of this into TIPS, increasing their share of the total TIPS outstanding from around 8% to 22.4%.

So, what happens when the Federal Reserve buys “inflation protected securities”? Think about it: the U.S. Treasury, at the behest of its political masters, spends money it doesn’t have on things politicians like but aren’t willing to raise taxes to pay for. This creates mountainous deficits, which must be funded somehow. Private investors, responsible for their own money or funds entrusted to them as fiduciaries, are insufficiently stupid to buy Treasury bonds to cover the gap, so the Federal Reserve, at the behest of its political masters, creates new money out of thin air (as trends analyst Gerald Celente says, “money that isn’t worth the paper it isn’t printed on) and uses it to buy these Treasury bonds. But it doesn’t just buy plain old bonds—it buys TIPS, whose principal and interest payments increase with inflation.

But what is inflation? As Milton Friedman said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Inflation is simply an increase in the money supply, which is precisely what the Federal Reserve is doing when it summons “dollars” from the void to buy these TIPS. But since they’re “inflation protected”, as the inevitable inflation created by the money printing kicks in, the value of the TIPS held by the Federal Reserve will increase, and the Treasury will need more “dollars” to pay the interest and principal upon maturity. So where do those “dollars” come from? By selling more TIPS to the Federal Reserve, of course!

Lather, rinse, repeat.

This is the fairy castle behind the “everything bubble" that began in 2020. The newly created money tends to flow first into liquid assets, driving bond yields down and equity (stock market) prices up. Then it gushes into the general economy and is seen in consumer prices, energy prices, real estate, durable goods such as automobiles, and finally in wages and salaries as workers demand raises to cope with the rising prices of everything. We are now coming into the final phases of this cycle, which closes upon itself as government response to rising prices results in more money printing.

It would be hilarious if it weren’t all so tragic for those who work hard and save.