Yesterday, 2021-11-15, the NASA Office of the Inspector General issued a report, “NASA’s Management of the Artemis Missions” [PDF]. Here are two key paragraphs from the “What We Found” section.

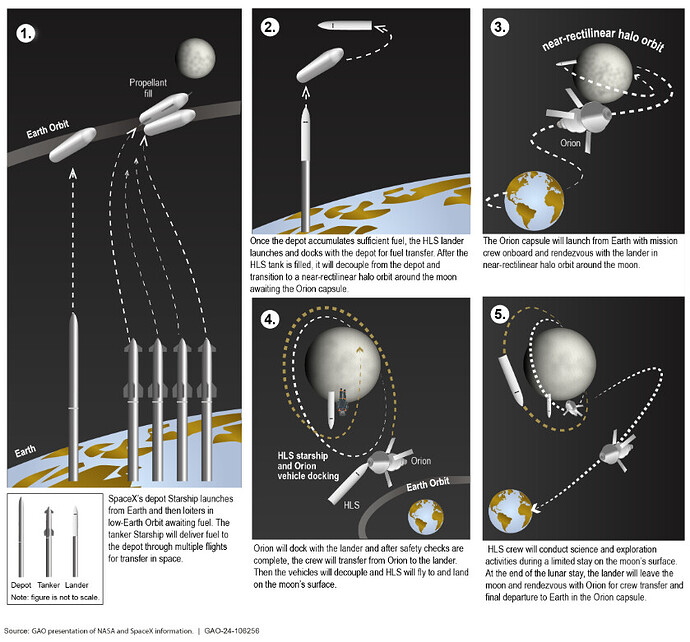

NASA’s three initial Artemis missions, designed to culminate in a crewed lunar landing, face varying degrees of technical difficulties and delays heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic and weather events that will push launch schedules from months to years past the Agency’s current goals. With Artemis I mission elements now being integrated and tested at Kennedy Space Center, we estimate NASA will be ready to launch by summer 2022 rather than November 2021 as planned. Although Artemis II is scheduled to launch in late 2023, we project that it will be delayed until at least mid-2024 due to the mission’s reuse of Orion components from Artemis I. … Given the time needed to develop and fully test the HLS and new spacesuits, we project NASA will exceed its current timetable for landing humans on the Moon in late 2024 by several years.

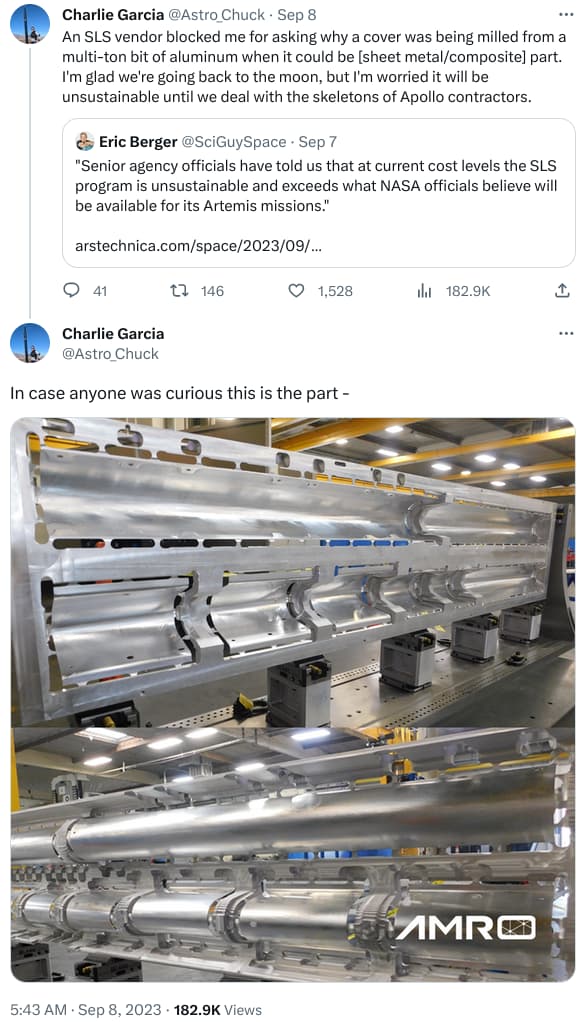

In addition, NASA lacks a comprehensive and accurate cost estimate that accounts for all Artemis program costs. For FYs 2021 through 2025, the Agency uses a rough estimate for the first three missions that excludes $25 billion for key activities related to planned missions beyond Artemis III. When aggregating all relevant costs across mission directorates, NASA is projected to spend $93 billion on the Artemis effort up to FY 2025. We also project the current production and operations cost of a single SLS/Orion system at $4.1 billion per launch for Artemis I through IV, although the Agency’s ongoing initiatives aimed at increasing affordability seek to reduce that cost. Multiple factors contribute to the high cost of ESD programs, including the use of sole-source, cost-plus contracts; the inability to definitize key contract terms in a timely manner; and the fact that except for the Orion capsule, its subsystems, and the supporting launch facilities, all components are expendable and “single use” unlike emerging commercial space flight systems. Without capturing, accurately reporting, and reducing the cost of future SLS/Orion missions, the Agency will face significant challenges to sustaining its Artemis program in its current configuration.

So, according to the NASA Inspector General, each SLS/Orion launch will cost US$ 4.1 billion which is, however you calculate it, between two and three times the cost of a Saturn V/Apollo launch in inflation-adjusted dollars. And this is supposed to be the heart of a “sustainable” lunar exploration program.

By comparison, Elon Musk recently estimated the cost per launch for Starship as around US$ 2 million, with US$ 900,000 of that being the liquid methane and oxygen propellants consumed by the rockets. So, if Starship works as intended, its cost per launch will be two thousand times less than NASA’s Space Launch System. With on-orbit refueling (which will require multiple Starship launches), it will be able to deliver 150 tonnes to a trans-lunar trajectory, while the Block I version of SLS has a capacity of 27 tonnes and the most advanced planned derivative, Block 2, whose development is not expected to start before the “late 2020s”, will increase this to 46 tonnes, less than a third of Starship.