As a boy I greatly enjoyed Khyber, British India’s North West Frontier: the story of an imperial migraine, by Charles Miller (1977)

The back cover gives a fair sample:

“Between a dust-layered blue turban and a shaggy, scrofulous black beard (usually dyed when it began to whiten) were fixed the eyes of a hawk, the teak of a vulture and the mouth of a shark. The owner of these features, as a rule, stood slightly taller than a jump center and moved with the silent grace of a tiger on a stalk. Beneath his long, unwashed white robe he was likely to have on a pair of tattered, ankle-length pajama pants and a loose, dirtcaked tunic festooned with charms and amulets. The cotton cummerbund holding trousers and tunic in place was also a repository for an oversize flintlock pistol, two or three knives and a long curved tulwar that could mince a floating feather. In addition to the sidearms, there was a long-barrelled jezail, held casually over the shoulder or cradled in the crook of the arm—always loaded and ready to fire. Roses, worn behind the ears, often rounded off the getup. They did nothing to dispel the notion that here was a creature whose sole purpose and pleasure in life was the inflicting of a death as uncomfortable and prolonged as it might be possible to arrange.”

The Pathan was formidible enough, but their Padshah made them tremble.

Many years after reading Khyber, I was amazed to learn that this ogre had written an autobiography (there were so few literate Afghans in the late 19th century that one could invite them all to dinner, and indeed Abdur Rahman often did). Not only that, but it reads like a boys-own adventure novel, followed by him turning into a sort of homocidal Connecticut Yankee in his own court. We’ll get to his Autobiography in due course, but Miller is too good not to quote at length.

Before I do though, it’s worth noting that Abdur Rahman’s legacy is still with us. He handed over to the British the territory containing all his most ungovernable Pathans, on the other side of what is still called the “Durand Line”, and is still the nominal border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. These Pathans are still ungovernable, the Pakistani Army doesn’t dare go in with fewer than 20,000 troops, and 50,000 is not considered excessive. These Pathans prevented both the USSR and the USA from conquering Afghanistan, and no doubt they have unwittingly helped India by keeping the Pakistani armed forces otherwise occupied.

[p. 223] Chapter 20: The Torturer at Home

The Amir Abdur Rahman Khan once told an Englishman named Frank Martin that during the course of his reign he had ordered the execution of more than 100,000 Afghans. Martin served for some years as Abdur Rahman’s chief civil engineer, and the book he wrote about his experiences with the Amir included a chapter entitled “Tortures and Methods of Execution,” whose subtitles read:

Khyber Ch. 20, continued:

“Hanging by hair and skinning alive . . . Beating to death with sticks . . . Cutting men in pieces . . . Throwing down mountain-side . . . Starving to death in cages . . . Boiling woman to soup and man drinking it before execution . . . Punishment by exposure and starvation . . . Burying alive . . . Throwing into soap boilers . . . Cutting off hands . . . Blinding . . . Tying to bent trees and disrupting . . . Blowing from guns . . . Hanging, etc.” Martin also noted that “there are other forms of torture . . . but these cannot be described.”

The most revolting aspect of these barbarities was that they were perpetrated in a good cause. When Abdur Rahman took up the reins of Afghanistan’s government in 1880, he found himself presiding over a state of unbridled anarchy. The firm foundations of order and unity built by his grandfather Dost Muhammad had begun to crack during the five-year war following the Dost’s death in 1863, had crumbled further under Sher Ali and Yakub Khan, and had finally collapsed altogether in the Second Afghan War and the British occupation. As in the decade before Dost Muhammad’s accession in 1826, Afghanistan had retrogressed to a mutilated balkaniza- tion that had stripped it of any pretensions to sovereignty. Once again, murderers did their dark deeds in bright sunlight while highwaymen bushwhacked caravans across the length and breadth of the land so thoroughly that trade had all but dried up. To the extent that any administration existed, it was being eaten alive by a corrupt elite of semiliterate civil servants called mirzas^ who feathered their nests by accusing other mirzas of swindling and then took huge bribes to withdraw the charges. It was always easy to make an indictment stick, said Martin, “for very few besides the mirzas can do more than count up to twenty.” Although the British had smiled on Abdur Rahman, he held even less power when he took the throne than had Dost Muhammad five decades earlier. Once again, the real rulers of Afghanistan were its tribal robber barons who held their provinces by duplicity and naked force, who mobilized huge armies against each other and kept the whole country in a state of perpetual vendetta. In such conditions, any amir who wished to restore order and assert a legitimate claim as de facto and de jure monarch could hardly be a stickler for parliamentary procedure. The task required a strong man. Abdur Rahman proved to be all of that. His priority need was to smash the power of the tribal warlords. He had got off to an excellent start in that direction even before Lytton and Roberts had offered him the Afghan throne [. . . .]

[p. 225] Abdur Rahman’s horsemen rode down the rebel troops and systematically cut them to pieces. Several thousand of the survivors were blinded with quicklime and Afghan Turkestan remained an integral part of the nation. When Abdur Rahman died in 1901, Afghanistan had been transformed from a henhouse of squabbling headmen into something like a sovereign state.

Abdur Rahman was no less diligent in his war on crime. Accurate records were never kept of the number of human hands lopped off with swords as punishment for theft, or of the deaths from shock when the blood-spurting stumps were plunged into boiling tar to prevent infection, but the figure probably ran into the scores of thousands. Executions were summary, although not always swift. A bandit caught waylaying a caravan could consider himself lucky if he was merely bayoneted to death or blown from the muzzle of Kabul’s noonday gun. Just as often, he could count on having several square inches of his skin removed daily, for as many days as it took him to succumb. Or he might be hanged, but not from the conventional drop-gallows with its split-second snapping of the neck. The condemned man was simply hauled up and allowed to strangle at leisure.

Other executions lasted even longer. Travelers crossing the Lataband Pass on the road between Kabul and Kandahar rode beneath a huge iron cage suspended from a pole; in it lay the bleaching bones of convicted highwaymen who had been placed there to advertise Abdur Rahman’s justice by dying of hunger, thirst, heat stroke, frostbite or all four. If the cage contained a still-living inmate, no one dared give him so much as a grain of millet or a drop of water. Minor offenses carried penalties that included the sewing together of upper and lower lips, rubbing snuff in the eyes, hanging by the heels for a week, nose amputations and whiskerplucking. The last was specially dreaded: a smooth-cheeked Muslim, unable to swear oaths by his beard, tended to feel like a quadriplegic. The two most important things about these sentences was that they were carried out on a massive scale—unprecedented even in Afghan history—and that they were public. Although the lesson did not get across instantly—“the boast of the true Afghan,” wrote Martin, “is that he can endure pain, even to death,’ without a sigh or sound, and some do so”—its impact was gradually felt and its results, in due course, became visible. By the 1890s, Abdur Rahman could write with a certain pride of the contrast between his highways, where caravans no longer needed armed escorts, and the Khyber Pass, “which the English have not been able to render safe for travellers, without a strong body-guard, even after sixty years’ rule.”

Of course, Abdur Rahman never eradicated crime completely; that would have been too much to expect among a people whose instincts for corruption, conspiracy and murder were a conditioned reflex. He was continually alive to potential insurgency in the highest councils of government and made it an article of policy to arrange for the secret garroting or throat-cutting of close advisers who seemed likely to emerge as rabble-rousers or plotters against him. He girded his person with an elaborate security apparatus, installing spies not only in every government department but in his own household. (Some close relatives had their own agents spying on the Amir.) Special guards stood round-theclock sentry duty over his food and drink; at mealtimes, all dishes placed before him were first tasted in his presence by the palace cook. Once, when he had a toothache, his surgeon told him that the extraction would take only twenty minutes with chloroform, whereupon Abdur Rahman ordered that the tooth be pulled without anesthetic, shouting angrily that he could not risk being out of the world for twenty seconds. But for all the imperfections of Abdur Rahman’s system, no ruler of Afghanistan had ever united the country more firmly or given its people a stronger sense of national unity—or made it more unmistakably clear who was in charge. And in so doing, Abdur Rahman also made himself the most feared individual in Central Asia.

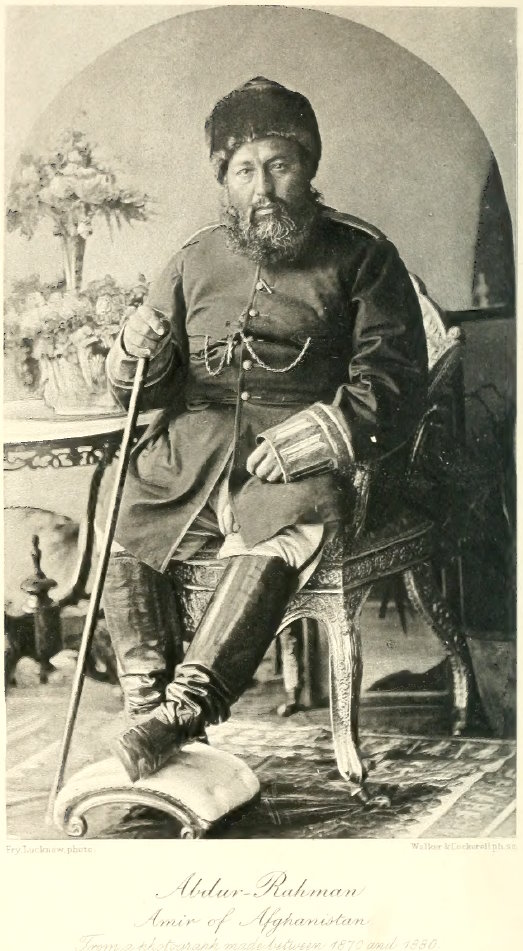

Certainly he looked the part. Even in his declining years, when he was racked by gout, wore badly fitting false teeth and dyed his huge beard black in accordance with Afghan custom, Abdur Rahman remained a bull-lion of a man. Martin described him as “very stout and broad, with a rather long body and short legs. His eyes were very dark, almost black, and looked out from under his heavy brows with quick, keen glances. . . .

[He] was always the king, and there was that about him which forbade any one taking advantage. . . . When roused to anger, his face became drawn, and his teeth would show until he looked wolfish, and then he hissed words rather than spoke them, and there were few of those before him who did not tremble when he was in that mood, for it was then that the least fault involved some horrible punishment.”

There was another side to Abdur Rahman’s character. He had a lively sense of humor and was a gifted raconteur who liked to tell jokes about himself. A favorite anecdote concerned his youthful affliction with a large intestinal worm, which no amount of therapy could dislodge until he put his own ingenuity to work. What he did, he liked to explain with elaborate gestures, was order a banquet laid out before him. The smell of the food tempted the worm, which then began to crawl up Abdur Rahman’s throat, enabling him to reach into his mouth and draw the worm all the wav out. When he told such tales, the throne room would quake with the thunder of his laughter.

Even his rages with miscreants could be tempered with whimsy. One of his generals, found guilty of some seemingly disloyal act, was cashiered and made to serve as a batcha, or palace dancing boy. When some gold was being counted in his treasury, Abdur Rahman noticed that a highranking cabinet minister had abstracted several coins and hidden them in his stocking. The Amir then made a deceptively casual remark about the mistaken belief among foreigners that Afghans were not whiteskinned, and asked the embezzling official to explode the fallacy by baring his leg. The perpetrator had no choice but to obey. To his great good fortune he was merely thrown into prison.

A more or less model family man, Abdur Rahman was deeply devoted to his five sons, even though he suspected their political ambitions and often treated them as upper-echelon bureaucrats rather than the fruit of his loins. He was Afghanistan’s chess and backgammon champion (possibly no one dared beat him), and his passion for flowers gave the royal palace in Kabul a resemblance to a scaled-up greenhouse even in winter. Music seemed to have charms that soothed the Amir’s savage breast. He himself played the violin and rebab passably well, and bragged in his autobiography that “it must be therefore a luxury and pleasure for my officials to be in my presence to enjoy all the various pleasures I provide for them.” Considering what else Abdur Rahman was capable of providing, the officials probably found the music more relief than enjoyment.

Abdur Rahman probably took his greatest pride in being a jack of all trades and master of some. Even as a child he had shown a mechanical aptitude rare among Afghans, teaching himself architecture, carpentry, blacksmithing and rifle-making before he began to grow whiskers. During his exile in Russian territory he continued his self-education, adding medicine, dentistry, watch-making, phrenology, gold-working and piano-tuning to his list of skills. He was a staunch upholder of the work ethic and often voiced contempt for the idle ways of other Asiatic princes. Even when prostrate with gout, he ran his country single-handedly. In 1894, Curzon visited Abdur Rahman in Kabul and wrote that “there was nothing from the command of an army or the government of a province to the cut of a uniform or the fabrication of furniture that he did not personally supervise and control.” If there had been railways in Afghanistan, he would have seen to it that they ran on time. [Note: There were none because Abdur Rahman feared that they might expedite the movement of Russian or British troops if either power ever decided to invade. To this day, (1977) there is not a single foot of rail in Afghanistan.] He worked a twenty-hour day, disregarding the pleas of his hakims and his two or three British doctors [Note: President Kennedy was not the first chief of state to have a woman physician, Abdur Rahman anticipated him when he hired Dr. Edith Hamilton from England.] to follow a less demanding schedule. “As I am a lover of the welfare of my nation,” he wrote, “I do not feel my own pains, but the pains and sufferings and weaknesses of my people.”

His people may not always have appreciated this concern for their betterment, and Abdur Rahman himself often despaired of ever succeeding in his attempt to drag them out of the Iron Age. (His own private secretary had a sixth-grade knowledge of reading and could barely compose a letter.) But he never stopped trying, and his reforms were by no means exclusively punitive. To make Afghanistan less dependent on imports, he hired expatriate technicians who studied the country’s mineral resources—particularly its gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, nickel and zinc. Other foreign specialists on his payroll laid the foundations of a rudimentary industrial system, training nomadic warriors in a variety of skilled trades. In Kabul’s flourishing workshops, Afghan mechanics and craftsmen not only mass-produced guns and ammunition for the armed forces but minted coins and turned out furniture, leather goods, European clothing and a proliferation of metalware. Abdur Rahman also offered cash prizes as incentives to good work, and if an Afghan wanted to go into business for himself, he could usually count on a generous interestfree loan from the Amir’s own pocket. It has been said that as many as 100,000 of Abdur Rahman’s countrymen found gainful employment in some sort of modern manufacture or commercial enterprise.

Above all, Abdur Rahman made himself accessible to every class of the populace. “It was usual,” wrote Martin, “for people to be allowed to present petitions when meeting him on the road, or returning from the musjid [mosquel on a Eriday (the Mussulman Sunday), and this he encouraged, and even went so far … as to call all men, even sweepers, ‘brother.’ ” At public durbars in the royal palace, the pleas and disputes of street beggars who came before Abdur Rahman received as much [p.229] attention and thoughtful adjudication as did the petitions of influential chiefs and wealthy merchants. Although some supplicants did not always have the few coppers needed to bribe the guards at the palace gate, no one was ever turned away deliberately by Abdur Rahman himself. It is quite possible that the fairness of the personal justice that he meted out may have compensated at least a little for his more barbaric excesses.

If Afghanistan’s backwardness exasperated Abdur Rahman, his sorest trial was the accident of his own birth, which in terms of his pugnacious instincts came at least a century too late and denied him the opportunity to emulate Genghis Khan. Curzon wrote of him as “a man who, had he lived in an earlier age and not been crushed, as he told me, like an earthenware pot between the rival forces of England and Russia, might have founded an Empire, and swept in a tornado of blood over Asia and even beyond it.” [Note: As a conqueror, he had to content himself with the annexation of a small cluster of mountains called Kafiristan, the setting of Kipling’s “The Man Who Would Be King.” He also acquired the Wakhan panhandle on Afghanistan’s extreme northeast frontier, although Wakhan was more or less forced on him by the British, who, oddly enough, did not want the icy outpost either.]

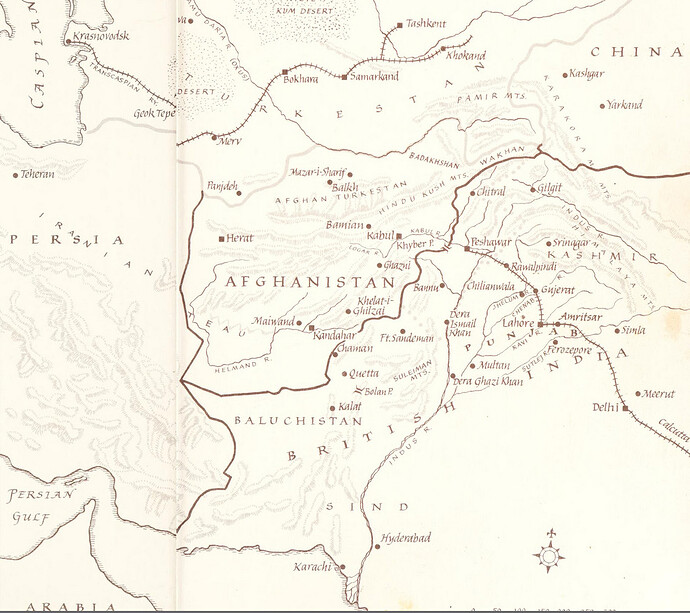

For the next quotation regarding the negotiation of the Durand Line, this map from the front inside cover of Khyber is helpful:

Abdur Rahman tricks the Brits

[p.240] Abdur Rahman did not simply sit back and place the Frontier’s fate in the hands of Allah. In the numerous protests he lodged during the 1890s with the Viceroy, Ford Fansdowne, he was sometimes almost polite, with veiled threats suggesting that British border policy was self-defeating. “In your cutting away from me these frontier tribes, who are people of my nationality and my religion,” said Abdur Rahman, “you will injure my prestige in the eyes of my subjects, and will make me weak and my weakness is injurious to your government.” But the Amir could also warn openly: “If at any time a foreign enemy appear on the borders of India, these frontier tribes will be your worst enemy.”

And Abdur Rahman would not have been Abdur Rahman had he confined himself to letter-writing. He also used his influence among the hill Pathans, which was not inconsiderable, to sow the seeds of anti- British discontent, which was not hard to do. “The Amir is behaving worse than ever,” wrote Sir Mortimer Durand in 1892. “He tells us he is King of the Afridis, and almost admits that he has stirred them up against us.” British counterprotests fell on deaf ears. “[Abdur Rahman] treats our envoy as a prisoner,” said Durand, “. . . and he won’t come to meet the Viceroy ‘like an Indian Chief’ … I cannot see where it is to end.”

Presently, however, Abdur Rahman seemed to have concluded that threats would get him nowhere. In the late summer of 1893, he astonished Fansdowne with a proposal that a conference be held in Kabul with a view to a formal, and final, delimitation of the border. This, of course, was agreeable to Fansdowne, who had found his plate full with Abdur Rahman’s ongoing intrigues among the Pathans. Durand was appointed to head up the Indian Government mission, and although he wrote that he expected Abdur Rahman to be “extremely unpleasant,” he added that “the thing must be done, and … I think I shall be able to persuade him … to be reasonable about our frontier.”

Durand got a welcome surprise. Arriving in Kabul in early November 1893, I looked in vain for my old acquaintance . . . with his Henry the Eighth face and ready scowl. I suppose the scowl is ready still when wanted, but the Amir of today is a quiet, gentlemanly man; his manner and voice so softened and refined that I could hardly believe that it [p.241] was really Abdur Rahman. I trust all his extreme pleasantness does not mean a proportionately stiff back in business matters.”

Nor did it. Although Abdur Rahman took the precaution of hiding one of his ministers behind a curtain to write a verbatim account of the proceedings, the frontier dispute was swiftly and amicably ironed out. On November 12, perhaps to Durand’s amazement, Abdur Rahman put his signature and seal on a treaty renouncing all claims to a band of territory extending from the Hindu Kush to the westernmost limits of Baluchistan. The area particularly included the Khyber and Bolan passes, together with the previously contested northwest frontier regions of Bajaur, Dir, Swat, Buner, Tirah, the Kurram Valley and VVaziristan. The treaty formalized the emergence of the British Empire’s longest land frontier next to the United States-Canadian border. It was a concession on a grand scale.

It was also not entirely explicable. With scarcely a demurral, Abdur Rahman had surrendered nearly all of the land in which the British presence had been stirring his anxieties and fury for years. At least one British historian has claimed that the agreement was signed under duress, and, although this cannot be ruled out, there is also reason to believe that the Amir may have been inadvertently bamboozled. “It is possible,” writes Fraser-Tytler, “that in spite of Durand’s careful and lucid explanations [Abdur Rahman] did not really take in all the implications of the line drawn on the map before him, but was too conceited to say so.”

Thus he simply may not have known how much he was giving away. In any case, the Frontier question was settled at last. Durand returned to India with a bright feather in his cap.

It hardly needs saying that the treaty created more problems than it solved. Although the 1893 boundary—commonly known as the Durand Fine—has not changed to this day, it has come under continual and often severe criticism for its flaws. Fraser-Tytler calls it “illogical from the point of view of ethnography, of strategy and of geography,” noting particularly that “it splits a nation in two, and it even divides tribes.” This arbitrary amputation could barely be justified, even on grounds of geopolitical expediency. Despite the cantankerous independence of the Frontier Pathans, they were by history, tradition, race, language and temperament Afghans. If their allegiance to the Amir was spotty at best, they were even less suited to becoming subjects of the Queen; trying to absorb them and their lands into British India was like trying to graft a cactus spine to the trunk of an oak tree.

Since this is getting long, I’ll save the Amir’s Autobiography for a following post.