Looking for a good read? Here is a recommendation. I have an unusual approach to reviewing books. I review books I feel merit a review. Each review is an opportunity to recommend a book. If I do not think a book is worth reading, I find another book to review. You do not have to agree with everything every author has written (I do not), but the fiction I review is entertaining (and often thought-provoking) and the non-fiction contain ideas worth reading.

Book Review

How Vietnamese Refugees Gardened to Become Vietnamese-Americans

Reviewed by Mark Lardas

September 15, 2024

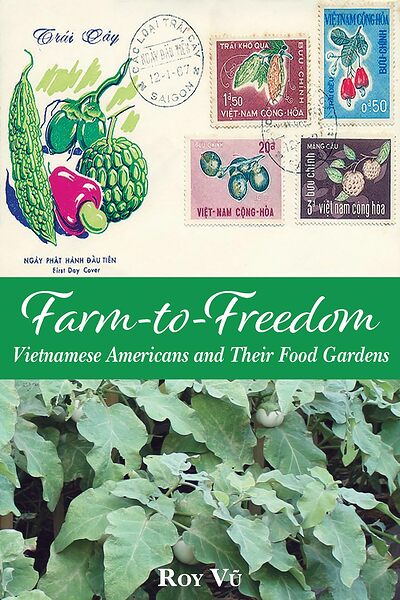

“Farm to Freedom: Vietnamese-Americans and Their Food Gardens,” by Roy Vu, Texas A&M University Press, 2024, 280 pages. $30.00 (Paperback), $14.95 (E-book)

Meet an immigrant from Vietnam in the US, especially one who arrived as a refuge after the Vietnam War, odds are they have a home garden. It may be a simple planter box in an apartment balcony or an elaborate several-acre microfarm. Not all of them, but enough that if you bet even money they did you would come out ahead long-term.

“Farm to Freedom: Vietnamese-Americans and Their Food Gardens,” by Roy Vu explains why. Vu is well placed to explain. The son of Vietnamese refugees, he arrived in the US as an infant.

Vietnam was (and remains) a largely culture. Even in its cities, inhabitants garden and raise chickens and rabbits. They are also hard-working. Visit Vietnam today and it seems every other person has a side hustle on top of the day job.

When the Vietnam War’s end caused two million in the south to flee Communism they brought those traits with them. Many brought native seeds. As Vu explains, in refugee camps in both Asia and the US, the first thing many did was plant gardens.

Gardens were a source of food, a demonstration of autonomy and empowerment and a way for homesick refugees to remind themselves of their forcibly abandoned homes. Bringing familiar Vietnamese cuisine with them grounded them in their new homes.

Once settled in the US they continued gardening. Food was plentiful but when they arrived starting in the 1970s traditional Vietnamese fruits, vegetables, and herbs were hard to find. Growing them in their own gardens made gave access to them and reduced grocery costs. It also made having a traditional family meal, with all members of the family present for dinner easier. (Once also an American tradition, it is increasingly abandoned today.) It helps them keep memories of Vietnam alive today, even as they become Americans.

Vu illustrates this in many ways. He peppers the book with original oral histories, community-based recipes and poetry, and photographs of home gardens in suburban and urban settings. He is a professor, so he also goes into discussions of culinary citizenship, food democracy, culinary justice, and food sovereignty. These excursions read more like genuflection to academic pieties than realistic concepts.

He also insists this behavior is unique to Vietnamese refugees. It is not. Vietnamese who immigrated to the US in this century are also dedicated gardeners. Virtually every set of rural immigrants share these traits. My grandparents’ generation, who came to the US in the 1920s from rural Greece all had backyard gardens filled with their cultural foods. One grandfather even had an eleven acre truck farm as a hobby. Vu concedes this in his epilog, where he discusses the farming practices of Congolese and Syrian refugees in the US.

While it has flaws “Farm-to-Freedom” is a worthwhile book. Vu sheds valuable light on the lives of the Vietnamese-Americans. It is a thought-provoking read.

Mark Lardas, an engineer, freelance writer, historian, and model-maker, lives in League City. His website is marklardas.com.