Looking for a good read? Here is a recommendation. I have an unusual approach to reviewing books. I review books I feel merit a review. Each review is an opportunity to recommend a book. If I do not think a book is worth reading, I find another book to review. You do not have to agree with everything every author has written (I do not), but the fiction I review is entertaining (and often thought-provoking) and the non-fiction contain ideas worth reading.

Book Review

Enigma Fully Revealed

Reviewed by Mark Lardas

December 4, 2022

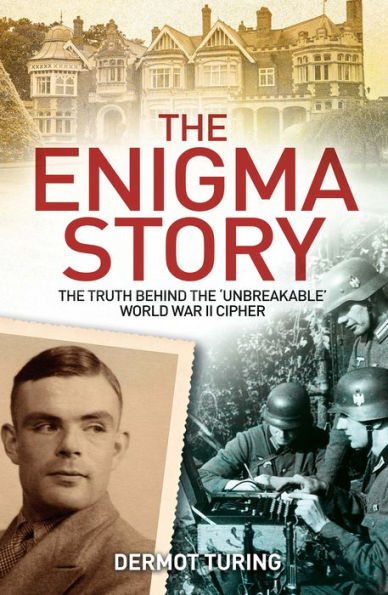

“The Enigma Story: The Truth Behind the ‘Unbreakable’ World War II Cipher,” by John Dermot Turing, Sirius, 2022, 240 pages, $12.99 (paperback), $8.99 (ebook)

One thing “everybody knows” about World War II is Allied cracking of the German Enigma code machine allowed the Allies to win World War II. It has become an article of faith since the secret was first revealed in the 1970s. Is that accurate?

“The Enigma Story: The Truth Behind the ‘Unbreakable’ World War II Cipher,” by John Dermot Turing tackles that question along with many others. It provides a fresh look at the history of Enigma, dispelling many myths and placing World War II codebreaking in proper historical context.

Turing opens the book with a history of the Enigma machine. He tells of its development in post-World War I Germany. Originally intended for commercial purposes, improved version were eventually used by the German government, and licensed abroad. (Italy’s military used a simpler version, while Britain used a much-improved version for their Typex coding machines.)

He explores the early efforts to crack Enigma. Pre-war, the Poles took the lead, using mathematics to decrypt messages. France also proved an early leader in decryption. Britain picked up the torch after Poland and France fell. It mechanized the process, although Turing shows the US industrialized decryption.

Turing uses sidebars to explain how decoding worked and to introduce the principal players in the decoding effort. A nephew of Alan Turing, the author places his famous uncle in the proper perspective. He shows that while Alan Turing played an important part in the story, other played bigger roles, including Gordon Welchman, whose contributions are almost totally neglected.

Turing also attacks the many myths that have sprouted up around codebreaking, many of which were created by prior authors with incomplete knowledge of the whole story. It turns out the British government did not allow Coventry to be bombed to protect the Ultra secret. Coded German messages never named their target. Similarly, the Poles never stole a machine from the Germans.

Turing also examines the role played by decryption in winning the war. He concludes in isolation it was not a war- or battle-winning weapon. (The British decrypted virtually the entire German battle plan for Crete and still lost.) He concludes it did shorten the war, leading to an Allied victory a year or two earlier than might otherwise have occurred.

“The Enigma Story” may be the most complete examination of the history of Enigma yet written. For those interested World War II codebreaking, it is a must-read book.

Mark Lardas, an engineer, freelance writer, historian, and model-maker, lives in League City. His website is marklardas.com.