Professor Charles I. (Chad) Jones of the Stanford Business School, developer of the Jones model for economic growth, has been investigating the consequences of a shrinking population, which now seems likely in many developed countries where the fertility rate has fallen (often dramatically) below the replacement rate. His 2022 paper in American Economic Review, “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population” [PDF] presents a model in which the interrelationships of population, innovation, and economic growth are explored. Here is the abstract.

In many models, economic growth is driven by people discovering new ideas. These models typically assume either a constant or growing population. However, in high income countries today, fertility is already below its replacement rate: women are having fewer than two children on average. It is a distinct possibility that global population will decline rather than stabilize in the long run. In standard models, this has profound implications: rather than continued exponential growth, living standards stagnate for a population that vanishes. Moreover, even the optimal allocation can get trapped in this outcome if there are delays in implementing optimal policy.

The video discusses the analysis in the paper and conclusions in a concise 20 minute presentation. If you’d like to be able to flip back and forth through the slides while watching the talk, here they are as a PDF.

This is a highly abstract and mathematical model. If you’re allergic to differential equations, this is probably not the paper for you. What is interesting for policy-oriented readers is that while the fertility rate is slightly above or below the replacement rate does not make a dramatic difference as perceived by families or a country in the short term,

The macroeconomics of the problem, however, make this distinction one of critical importance: it is the difference between an Expanding Cosmos of exponential growth in both population and living standards and an Empty Planet, in which incomes stagnate and the population vanishes.

further:

When the equilibrium fertility rate is negative, the optimal allocation typically features two stable steady states. If the economy adopts the optimal allocation soon enough, it converges to the Expanding Cosmos. But if the economy waits too long to switch, even the optimal allocation can be trapped by the Empty Planet outcome.

This means there is a point of no return after which changing policies has no effect on the outcome. The model shows that once population shrinkage begins, the flow of new ideas drops to zero, so sanguine predictions that “we’ll cope with that when we get there” or utopian fantasies of “degrowth” may not have worked out the consequences of an end to innovation on—everything.

Robin Hanson of George Mason University, who recommended this paper, discusses the consequences of a shrinking population and economy in a 2023-08-21 Substack post, “Shrinking Economies Don’t Innovate”.

This view has a dramatic implication for a world of low fertility, and thus falling population. If the world economy reaches a peak and then falls to a level that is only X% of that peak, but stays within the same growth mode, then at that point the rate of innovation would be no more than X% of the prior peak rate. Fewer than X% of N typical innovations would be found per year.

That is, in a shrinking economy, innovation grinds to a halt! And if after a shrinking economy, economic growth should restart, then a restart of innovation would be delayed until the new economy rose to pre-population-fall levels. If a culture of innovation had withered in the meantime, such a restart might take even longer.

⋮

Thus once we have entered into a shrinking world economy, we cannot put much hope on tech or innovation solutions. If such solutions are not found before the economic decline, they will probably never be found.

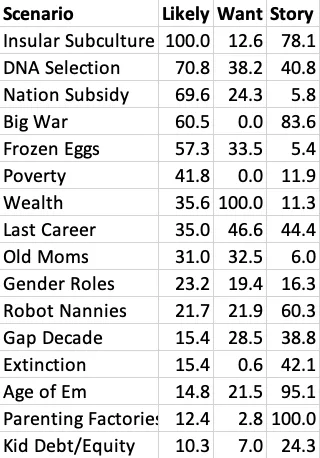

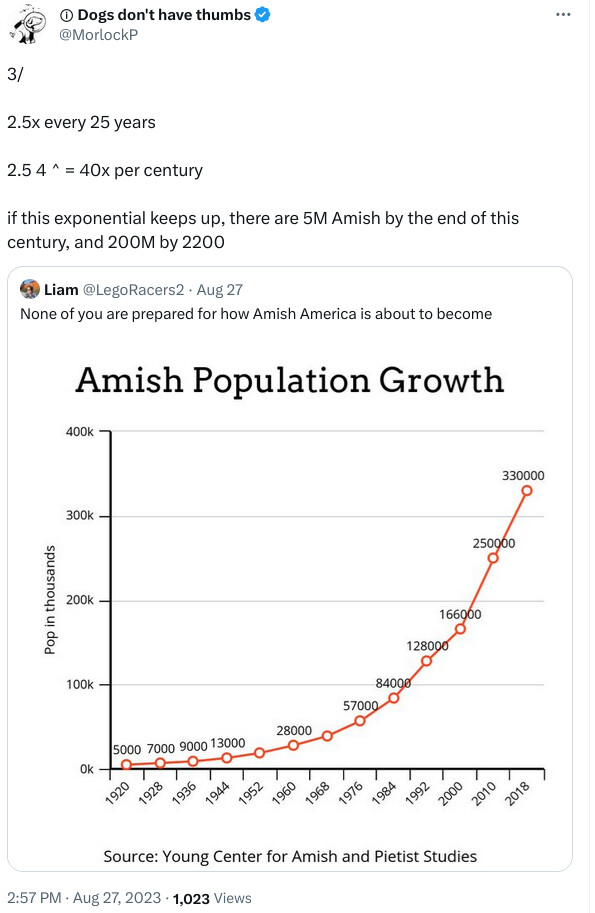

This, then, motivated him to ask, since we now appear to be in an age of below-replacement fertility, implying a shrinking population in the future, what are the possible scenarios for the future? Either the human population will continue to decline towards extinction or, at some point, fertility will rise and stabilise the population or resume growth. In a Substack post on 2023-08-24, “16 Fertility Scenarios”, he enumerated sixteen possible futures he could envision and presented the results of a battery of 𝕏 polls he posted, asking respondents to rank scenarios based upon their likelihood, desirability, and story potential of that outcome. Analysis of the results was complicated by the limit on four items in an 𝕏 poll, but the 2732 responses to 24 polls were as summarised below. See the paper cited above for detailed descriptions of each scenario.

Now, as I noted above, these are studies in macroeconomics, a subject which is particularly prone to “assume a cow is a sphere”: radical simplification of matters which involve a bewildering amount of detail and complicated and difficult to untangle interactions in the real world. For example, production of ideas is assumed to be proportional to population: the more people, the more ideas. Then, income per person is proportional to the accumulated production of ideas. But, one wonders, what people, and what ideas lie behind the letters in these equations? Certainly that matters, doesn’t it? Can a technological society confronted with a shrinking population solve its problems by importing hordes of low-IQ savages from those countries seemingly trapped in an eternal state of "developing”? Are new ideas for energy sources, manufacturing processes, materials for fabrication, and ways to organise complex endeavours the peer of innovations in deconstruction of literary and artistic works, eliminating embarrassing and distasteful episodes from recorded history, revising language to deny objective reality, or “remxing” the creative output of earlier ages into derivative works?

I present these analyses because they are interesting and pose challenges to commonly-held views of the future and rarely-questioned assumptions about the consequences of trends which now appear to firmly established. These are not my analyses, and I am not here to defend them, but purely to commend them to your examination and independent consideration.