2250 words from Report to Greco

REPORT TO GRECO

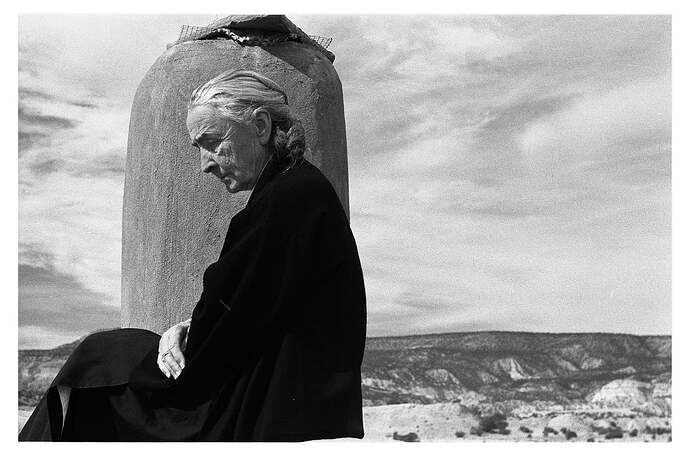

Nikos Kazantzakis

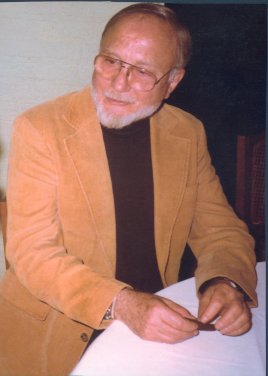

Translated by Peter A. Bien

INTRODUCTION:

THE WRITING OF “REPORT TO GRECO

by Helen N. Kazantzakis

NIKOS KAZANTZAKIS asked his God for ten additional years, ten additional years in which to complete his work—to say what he had to say and “empty himself.” He wanted death to come and take only a sackful of bones. Ten years were enough, or so he thought.

But Kazantzakis was not the kind who could be “emptied.” Far from feeling old and tired at the age of seventy-four, he considered himself rejuvenated, even after his final adventure, the tragic vaccination. Freiburg’s two great specialists, the hematologist Heilmeyer and the surgeon Kraus, concurred in this opinion.

The whole of the final month Professor Heilmeyer shouted triumphantly after each visit, “This man is healthy, I tell you! His blood has become as sound as my own!”

“Why do you run like that!” I kept scolding Nikos, afraid that he might slip on the terrazzo and break a bone.

“Don’t worry, Lénotska, I’ve got wings!” he answered. One sensed the confidence he had in his constitution and his soul, which refused to bite the dust.

Sometimes he sighed, “Oh, if only I could dictate to you!” Then, grasping a pencil, he would try to write with his left hand. “What’s the hurry? Who is chasing you? The worst is past. In a few days you’ll be able to write to your heart’s content.”

He would turn his head and gaze at me for a few moments in silence. Then, with a sigh: “I have so very much to say. I am being tormented again by three great themes, three new novels. But first I’ve got to finish Greco.”

“You’ll finish it, don’t worry.”

[…]

Now I remember another crucial moment in our lives, another hospital, this time in Paris. Nikos gravely ill again with a temperature of 104, the physicians all in a turmoil. Everyone had lost hope; only Kazantzakis himself remained unperturbed.

“Will you get a pencil, Lénotska? . . .”

Still plunged in his vision, he dictated to me in a broken voice the Franciscan haikai he placed in the saint’s mouth: “

I said to the almond tree,

‘Sister, speak to me of God.’

And the almond tree blossomed.

[…]

No, he did not manage to finish the Report to Greco in time; he was unable to write a second draft, as was his custom.

[…]

Alone, now, I re-experience the autumn twilight which descended ever so gently, like a small child, with the first chapter.

“Read, Lénotska, read and let me hear it!”

I collect my tools: sight, smell, touch, taste, hearing, intellect. Night has fallen, the day’s work is done. I return like a mole to my home, the ground. Not because I am tired and cannot work. I am not tired. But the sun has set. . . .

I could go no further; a lump had risen in my throat. This was the first time Nikos had spoken about death.

“Why do you write as though ready to die?” I cried, truly despondent.

And to myself: Why, today, has he accepted death?

“Don’t be alarmed, wife, I’m not going to die,” he answered without the slightest hesitation. “Didn’t we say I’d live another ten years? I need ten more years!” His voice was lower now. Extending his hand, he touched my knee. “Come now, read. Let’s see what I wrote.”

To me he denied it, but inwardly, perhaps, he knew. For that very same night he sealed this chapter in an envelope together with a letter for his friend Pantelís Prevelakis: “Helen could not read it; she began to cry. But it is good for her—and for me also—to begin to grow accustomed . . .”

[…]

His round, round eyes pitch black in the semidarkness and filling with tears, he used to say to me, “I feel like doing what Bergson says—going to the street corner and holding out my hand to start begging from the passers-by: ‘Alms, brothers! A quarter of an hour from each of you.’ Oh, for a little time, just enough to let me finish my work. Afterwards, let Charon come.”

Charon came—curse him!—and mowed Nikos down in the first flower of his youth! Yes, dear reader, do not laugh. For this was the time for all to flower and bear fruit, all he had begun, the man you so loved and who so loved you, your Nikos Kazantzakis.

—H.N.K.

Geneva, June 15,1961.

AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION

My Report to Greco is not an autobiography. […]

…this bloody track will be the only trace left by my passage on earth. Whatever I wrote or did was written or performed upon water, and has perished.

I call upon my memory to remember, I assemble my life from the air, place myself soldier-like before the general, and make my Report to Greco. For Greco is kneaded from the same Cretan soil as I, and is able to understand me better than all the strivers of past or present. Did he not leave the same red track upon the stones?

THREE KINDS OF SOULS, THREE PRAYERS:

1. I AM A BOW IN YOUR HANDS, LORD. DRAW ME, LEST I ROT.

2. DO NOT OVERDRAW ME, LORD. I SHALL BREAK.

3. OVERDRAW ME, LORD, AND WHO CARES IF I BREAK!

PROLOGUE

I COLLECT MY TOOLS: sight, smell, touch, taste, hearing, intellect. Night has fallen, the day’s work is done. I return like a mole to my home, the ground. Not because I am tired and cannot work. I am not tired. But the sun has set.

The sun has set, the hills are dim. The mountain ranges of my mind still retain a little light at their summits, but the sacred night is bearing down; it is rising from the earth, descending from the heavens. The light has vowed not to surrender, but it knows there is no salvation. It will not surrender, but it will expire.

I cast a final glance around me. To whom should I say farewell? To what should I say farewell? Mountains, the sea, the grape-laden trellis over my balcony? Virtue, sin? Refreshing water? . . . Futile, futile! All these will descend with me to the grave.

To whom should I confide my joys and sorrows—youth’s quixotic, mystic yearnings, the harsh clash later with God and men, and finally the savage pride of old age, which burns but refuses until the death to turn to ashes? To whom should I relate how many times I slipped and fell as I clambered on all fours up God’s rough, unaccommodating ascent, how many times I rose, covered with blood, and began once more to ascend? Where can I find an unyielding soul of myriad wounds like my own, a soul to hear my confession?

Compassionately, tranquilly, I squeeze a clod of Cretan soil in my palm. I have kept this soil with me always, during all my wanderings, pressing it in my palm at times of great anguish and receiving strength, great strength, as though from pressing the hand of a dearly loved friend. But now that the sun has set and the day’s work is done, what can I do with strength? I need it no longer. I hold this Cretan soil and squeeze it with ineffable joy, tenderness, and gratitude, as though in my hand I were squeezing the breast of a woman I loved and bidding it farewell. This soil I was everlastingly; this soil I shall be everlastingly. O fierce clay of Crete, the moment when you were twirled and fashioned into a man of struggle has slipped by as though in a single flash.

What struggle was in that handful of clay, what anguish, what pursuit of the invisible man-eating beast, what dangerous forces both celestial and satanic! It was kneaded with blood, sweat, and tears; it became mud, became a man, and began the ascent to reach—To reach what? It clambered pantingly up God’s dark bulk, extended its arms and groped, groped in an effort to find His face.

And when in these very last years this man sensed in his desperation that the dark bulk did not have a face, what new struggle, all impudence and terror, he underwent to hew this unwrought summit and give it a face — his own!

But now the day’s work is done; I collect my tools. Let other clods of soil come to continue the struggle. We mortals are the immortals’ work battalion. Our blood is red coral, and we build an island over the abyss. God is being built. I too have applied my tiny red pebble, a drop of blood, to give Him solidity lest He perish—so that He might give me solidity lest I perish. I have done my duty.

Farewell!

Extending my hand, I grasp earth’s latch to open the door and leave, but I hesitate on the luminous threshold just a little while longer. My eyes, my ears, my bowels find it difficult, terribly difficult, to tear themselves away from the world’s stones and grass. A man can tell himself he is satisfied and peaceful; he can say he has no more wants, that he has fulfilled his duty and is ready to leave. But the heart resists. Clutching the stones and grass, it implores, “Stay a little!”

I fight to console my heart, to reconcile it to declaring the Yes freely. We must leave the earth not like scourged, tearful slaves, but like kings who rise from table with no further wants, after having eaten and drunk to the full. The heart, however, still beats inside the chest and resists, crying, “Stay a little!”

Staying, I throw a final glance at the light; it too is resisting and wrestling, just like man’s heart. Clouds have covered the sky, a warm drizzle falls upon my lips, the earth is redolent. A sweet, seductive voice rises from the soil: “Come . . . come . . . come . . .”

The drizzle has thickened. The first night bird sighs; its pain, in the wetted air, tumbles down ever so sweetly from the benighted foliage. Peace, great sweetness. No one in the house . . . Outside, the thirsty meadows were drinking the first autumn rains with gratitude and mute well-being. The earth, like an infant, had lifted itself up toward the sky in order to suckle.

I closed my eyes and fell asleep, holding the clod of Cretan soil, as always, in my palm. I fell asleep and had a dream.

[…]

“Give me a command, beloved grandfather.”

Smiling, you placed your hand upon my head. It was not a hand, it was multicolored fire. The flame suffused my mind to the very roots.

“Reach what you can, my child.”

Your voice was grave and dark, as though issuing from the deep larynx of the earth.

It reached the roots of my mind, but my heart remained unshaken.

“Grandfather,” I called more loudly now, “give me a more difficult, more Cretan command.”

Hardly had I finished speaking when, all at once, a hissing flame cleaved the air. The indomitable ancestor with the thyme roots tangled in his locks vanished from my sight; a cry was left on Sinai’s peak, an upright cry full of command, and the air trembled:

“Reach what you cannot!”

I awoke with a terrified start. Day had already begun.

[…]

General, the battle draws to a close and I make my report. This is where and how I fought.

[…]

You will see my soul, will weigh it between your lanceolate eyebrows, and will judge. Do you remember the grave Cretan saying, “Return where you have failed, leave where you have succeeded”? If I failed, I shall return to the assault though but a single hour of life remains to me. If I succeeded, I shall open the earth so that I may come and recline at your side. Listen, therefore, to my report, general, and judge.

1

ANCESTORS

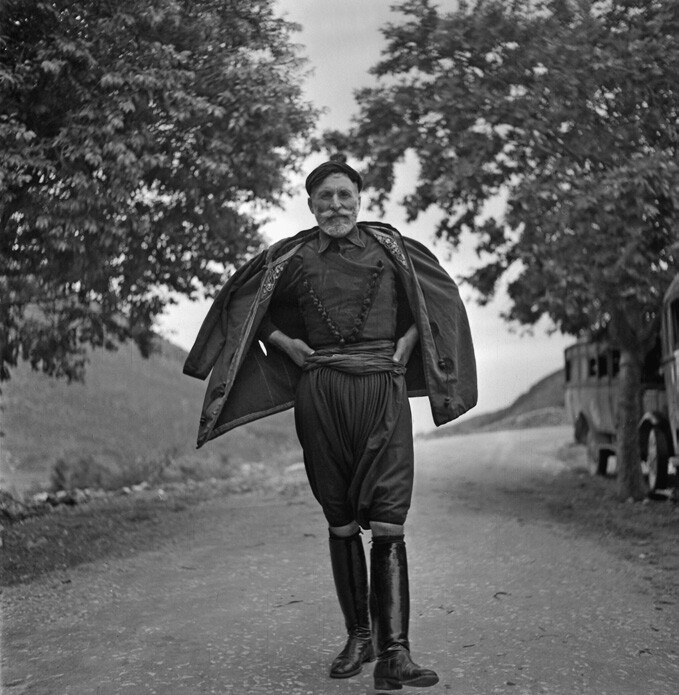

I LOOK DOWN into myself and shudder. On my father’s side my ancestors were bloodthirsty pirates on water, warrior chieftains on land, fearing neither God nor man; on my mother’s, drab, goodly peasants who bowed trustfully over the soil the entire day, sowed, waited with confidence for rain and sun, reaped, and in the evening seated themselves on the stone bench in front of their homes, folded their arms, and placed their hopes in God.

Fire and soil. How could I harmonize these two militant ancestors inside me?

I felt this was my duty, my sole duty: to reconcile the irreconcilables, to draw the thick ancestral darkness out of my loins and transform it, to the best of my ability, into light.

Is not God’s method the same? Do not we have a duty to apply this method, following in His footsteps? Our lifetime is a brief flash, but sufficient.

Without knowing it, the entire universe follows this method. Every living thing is a workshop where God, in hiding, processes and transubstantiates clay. This is why trees flower and fruit, why animals multiply, why the monkey managed to exceed its destiny and stand upright on its two feet. Now, for the first time since the world was made, man has been enabled to enter God’s workshop and labor with Him. The more flesh he transubstantiates into love, valor, and freedom, the more truly he becomes Son of God.