Here is an article from Smithsonian magazine which describes the Ranger “Lunar capsule”.

But the JPL engineers knew that solid rockets, while simpler than liquid-fuel ones, were also more unpredictable. No one could be sure a solid rocket would deliver the amount of braking needed to counteract all of the lander’s excess speed. Furthermore, nobody knew how to predict precisely how fast the spacecraft would be going relative to the moon, or even the exact location of the moon itself.

With all these uncertainties, Burke figured that Ranger might strike the moon at speeds up to 200 mph. He and his team began talking about developing a rugged spherical capsule capable of withstanding such an impact. If this “survival package” seemed a less than elegant plan for humanity’s first landing on the moon, Burke didn’t mind. “All we were thinking about,” he says, "was ‘Let’s get a transmitter down so we can prove we’re there.’ "

But how to protect sensitive scientific instruments from a crash as violent as an Indy race car hitting a concrete wall? To identify the best energy absorber, a variety of materials, including aluminum honeycomb, cardboard, and, in Burke’s words, “anything crushable,” were subjected to tests such as being dropped from a helicopter and slammed around with laboratory equipment. The victor, by a surprisingly wide margin, proved to be blocks of balsa wood, oriented with the end grain radiating out around the sphere for maximum energy absorption.

By the summer of 1960, a 26-inch-diameter sphere weighing 92 pounds began to take shape at a division of the Ford Motor Company in Newport Beach, California. Attached to the capsule would be a solid-fuel retrorocket, which was to ignite when Ranger was 10 miles above the moon. Ten seconds later, after slowing the lander almost to a hover, the rocket would burn out and be cast off. Pulled by the moon’s gentle gravity, the sphere would fall the remaining 1,100 feet to the surface, striking at a speed of about 75 mph. Cushioned by a six-inch layer of balsa wood, the lander would bump and roll to a stop. Inside, floating on a thin layer of water, a one-foot-diameter fiberglass sphere containing a seismometer, radio, and batteries would right itself and begin transmitting.

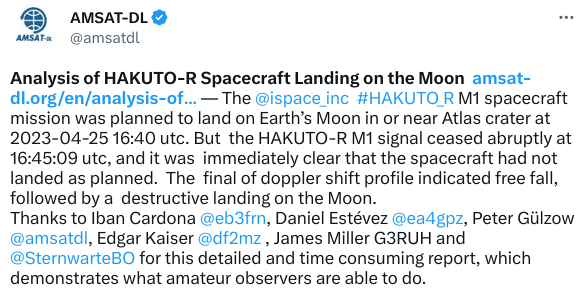

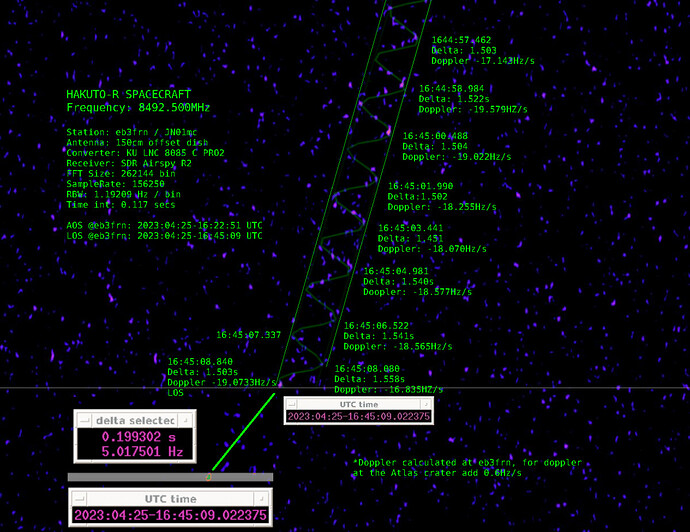

After three consecutive failures (all of which occurred before the landing capsule even had a chance to be tried), Ranger was redesigned into a pure impactor with six cameras, deleting the hard landing capsule. The first two of these failed as well, with the first success being Ranger 7, which impacted the Moon on 1964-07-31 at 13:25:48.82 UTC (love that precision!) at a velocity of 2.62 km/sec.

Here is contemporary newsreel coverage of Ranger 7. The lunar photo quality is what we saw at the time. Years later, the data were re-processed digitally and higher quality imagery was extracted. The spacecraft shown at the start of the newsreel is a Ranger, but not Ranger 7—the one shown has the landing capsule, which was deleted on Rangers 5 and later.

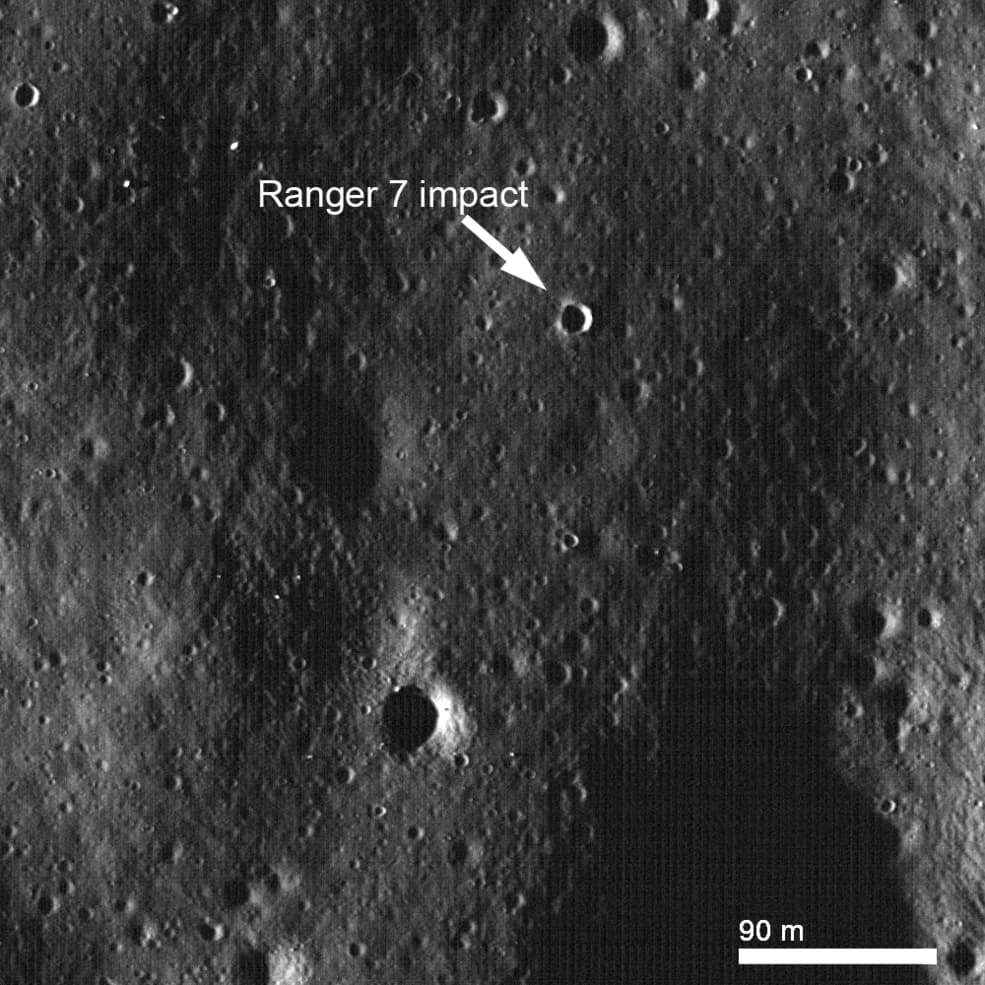

Here is the crater made by Ranger 7’s impact on the Moon, imaged by Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2018.