On 2022-07-04, The Network State by Balaji S. Srinivasan, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz and former Chief Technical Officer at Coinbase, was published. The book may be purchased in a Kindle edition from Amazon via the link above or may be read on-line at The Network State Web site, or downloaded in PDF form for free from that site.

Here, from the “Quickstart” chapter, is “The Network State in One Sentence”. Informally,

A network state is a highly aligned online community with a capacity for collective action that crowdfunds territory around the world and eventually gains diplomatic recognition from pre-existing states.

or, more exhaustively at the cost of additional words and commas:

A network state is a social network with a moral innovation, a sense of national consciousness, a recognized founder, a capacity for collective action, an in-person level of civility, an integrated cryptocurrency, a consensual government limited by a social smart contract, an archipelago of crowdfunded physical territories, a virtual capital, and an on-chain census that proves a large enough population, income, and real-estate footprint to attain a measure of diplomatic recognition.

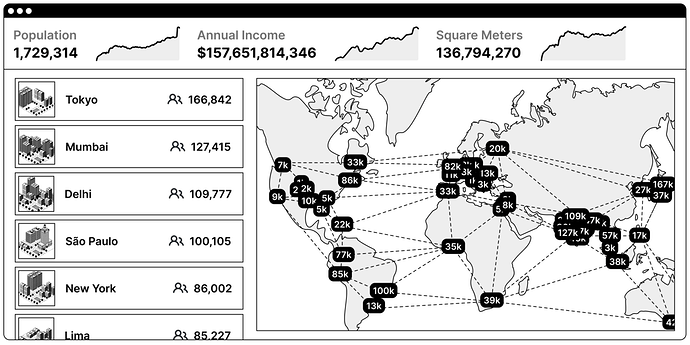

For the visually inclined, here is The Network State in One Image, illustrating a mature network state organised around a shared principle, with population, income, and territory controlled (in a global archipelago of bits and pieces) that rank it among many classic Westphalian-model nation states in existence today.

Here is how it might grow in the first few steps from a single founder and Working Paper.

I only started reading this 460 page book yesterday during a particularly hideous day of “trains, planes, and automobiles”, and I’m only a quarter of the way through, but so far I have found it superbly written (not to mention beautiful—it was produced in LaTeX), insightful, and bristling with links to original sources, many of which I was unaware.

The author argues that human social organisation on scales larger than hunter-gatherer bands seems to require a shared belief in a force greater than the individual, for which he uses the term “Leviathan”. For much of history, Leviathan was God, with the belief that behaviour which damaged the social fabric would be punished either by direct divine intervention or in an afterlife. The reason people wanted their masters and leaders to be “God fearing” was literal—that a ruler who feared that God will damn him to eternal torment in Hell could be trusted to behave morally and rule wisely even when nobody was looking or had the ability to counter his actions.

As religious belief weakened after the Enlightenment in the West and comparable transitions in other cultures and societies, Nietzsche famously proclaimed “God is dead”, which the author interprets as meaning that belief in God no longer constrained the actions of individuals, especially those in power. With this, and increasing centralisation, a new Leviathan, the State, emerged, with many people replacing their belief in an omnipotent God with fealty to an omnipotent State. While this was explicit under totalitarian regimes which actively suppressed religion as a competing Leviathan, it is increasingly common in nominally “free” societies where a State which is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent (albeit incompetent and inefficient) is accepted as an invariant part of the natural order by billions of people.

But, starting in the first decade of the twenty-first century, there’s a new Leviathan in town, the Network, and it is beginning to disrupt the institutions built around the two incumbent Leviathans. “The Internet never forgets” has become a commonplace observation and has led to the downfall of many who assumed media complicity would allow them to change the past to their advantage. The advent of blockchain technology in 2009 has provided a combination of technological and social organisation which provides an unalterable historical record (a “log file” if you will, complete with trusted time stamps) which can serve as an oracle of what really happened, as opposed to what Church and State would prefer to have you believe.

At the same time, the Network both allows affinity groups to self-organise without the constraints of geographical borders while using cryptography and verifiable reputation and trust systems to erect their own borders to protect themselves from infiltration and subversion.

Over all of human history, we have had only two widely successful and distributed Leviathans so far: God and State. We may be living through a period where a viable competitor is emerging which will allow new spontaneous forms of self-organisation that compete with legacy institutions, just at the time when those institutions are visibly failing in many regards and are losing legitimacy among those subject to their power.

Ours are interesting times, and this book appears to offer valuable insights on what is happening and what may come next.