It’s been a bit over a month since the Great Summer Superconductor Flap of 2023 erupted, and since room temperature superconductors are no longer the Current Thing, they’ve largely disappeared from the news. So now, maybe it’s time to start asking:

Room Temperature Superconductivity — Might There Be Something There After All?

I’ve been expecting this to happen. After the rise and fall of “cold fusion” in 1989, sporadic reports of replications and other experiments indicating something anomalous was going on continued for years, with Infinite Energy magazine, amidst breathy reports of “over-unity” devices and zero-point energy, continued to report on work in "low-energy nuclear reactions”. And even now (quoting from the Wikipedia article):

For example, it was reported in Nature, in May, 2019, that Google had spent approximately $10 million on cold fusion research. A group of scientists at well-known research labs (e.g., MIT, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, and others) worked for several years to establish experimental protocols and measurement techniques in an effort to re-evaluate cold fusion to a high standard of scientific rigor. Their reported conclusion: no cold fusion.

In 2021, following Nature’s 2019 publication of anomalous findings that might only be explained by some localized fusion, scientists at the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Indian Head Division announced that they had assembled a group of scientists from the Navy, Army and National Institute of Standards and Technology to undertake a new, coordinated study. With few exceptions, researchers have had difficulty publishing in mainstream journals. The remaining researchers often term their field Low Energy Nuclear Reactions (LENR), Chemically Assisted Nuclear Reactions (CANR), Lattice Assisted Nuclear Reactions (LANR), Condensed Matter Nuclear Science (CMNS) or Lattice Enabled Nuclear Reactions; one of the reasons being to avoid the negative connotations associated with “cold fusion”. The new names avoid making bold implications, like implying that fusion is actually occurring.

Ahhhh, yes, the Americans forever changing the names of things to avoid notoriety.

Anyway, here we go with room temperature superconductivity. Here is an opening shot from Tom’s Hardware on 2023-08-24.

But the field of superconductors is a fast-changing one. Newly-published, pre-print theoretical research generally continues to support LK-99 as having the properties required to become a superconductor; and now, internet sleuths have discovered a Korean-language update on the original LK-99 patent. This document presents further details (and also new questions) regarding the synthesis process, even as the original Korean authors reaffirm the significance (and veracity) of their discovery.

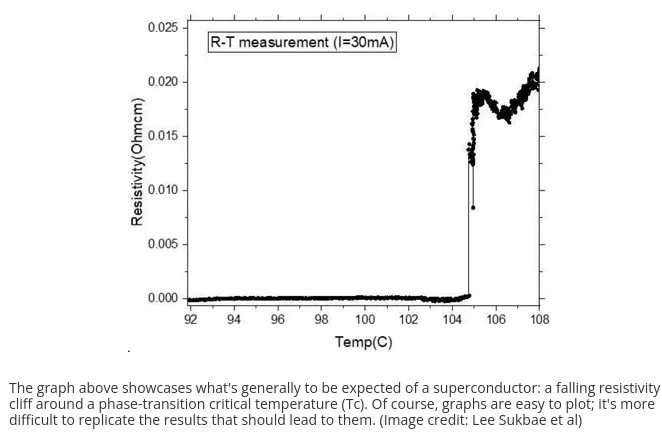

Unfortunately, what we’re still left with is an incomplete picture of LK-99 - one that will seemingly require much more effort in understanding than some would lead us to believe. But the paper does have what’s required: a graph plotting LK-99’s resistivity. Crucially, the graph says it does drop to zero.

⋮

But it seems that solid state synthesis wasn’t how Lee’s team discovered the (alleged) emergent superconductivity of LK-99. This was done through a technique known as vapor deposition; through it, the same compounds were reacted, but instead of the objective being to end up with an LK-99 crystal, the technique instead allows for the reaction’s vapors to collect against a glass structure, creating a thin film of the compound. According to Sukbae and his team, this film is forged in the 100 degrees Celsius - 400 degrees Celsius temperature range (with a black film of lead sulfide (PbS) in the lower temp area, a white film of lanarkite (Pb2SO5) in the higher temp area, and a gray film of lead appatite in the intermediate area.

It’s from this gray lead-apatite, micron-thick film that the authors insist room-temperature, ambient-pressure superconductivity emerges. The authors also pre-emptively refer state that impurities of iron (Fe) and other elements also emerge from the synthesis process, and that these impurities are well-known sources of ferromagnetism and diamagnetism - some of the features other studies have already encountered and replicated.

But it may have been premature to consider those results as proof that LK-99 is a dud. According to the authors, these magnetic features make it more difficult to see the actual Meissner Effect in action, with less cautious onlookers assuming that LK-99’s levitation capabilities ended at those types of magnetism.

⋮

Which brings us to the latest paper from Vayssilov et al at Sofia University, which also suggests that LK-99 could have the required properties to become a superconductor (do note that once again, there’s no mention of room-temperature or ambient-pressure). The general idea presented in the paper is that there are two ways that could happen: by removing certain oxygen atoms from their places, potential highways for superconductivity appear, with space that was previously occupied by atomic nuclei now being open for electron pairs (the so-called Cooper pairs) to skirt around. Another proposal from the paper is that this same effect can be achieved through the Cu doping we’ve talked about.

Here is the theoretical paper from ChemRxiv, “Alternative Concept of One-Dimensional Superconductivity – Key Role of Defects Revealed by Quantum Chemical Calculations of Lead Apatite” (full text at link). This is the abstract.

Doped lead apatite has been recently reported to feature superconductivity at room temperature and ambient pressure, which may have huge impact on the progress of the humanity in general. The first principle calculations, aiming at understanding the reasons for such behavior, suggest that reduced form of undoped and copper-doped lead apatite contain one dimensional channels, which are free of ions, but with electrostatic potential inside providing conditions for unimpeded electron mobility, potentially leading to superconductivity. Key aspect is that channels are surrounded by lead cations, which generate the necessary electrostatic field but due to their high atomic mass have reduced mobility and do not block the channels even at ambient temperature. Our observations on the modeled structures allowed us to present an alternative concept for features, giving rise of the superconductivity based on chemical understanding of the structure and frontier orbital of the material.

From the start, I found it intriguing that some of the original papers mentioned using vapour deposition as a way to produce uniform material rather than the synthesis process that appears to yield a composite made up of different substances, only some of which exhibit the unusual properties. It will be interesting to see if replications using that (more difficult) technique produce promising results.