Does this indicate there may be a room temperature superconductor lurking in some regions of this notoriously difficult to prepare material? Andrew Côté posted a quick look analysis in a mega-𝕏 post, which I reproduce here as text in the interest of readability and ease of quoting.

A paper was published this morning by a collaboration of two different teams looking to confirm or invalidate the original LK-99 superconductivity result.

Here’s everything you need to know:

-

A room temperature superconductor would be an invention on-par with the transistor, or perhaps even greater, for its ability to revolutionize every technology that uses electricity.

-

LK99 was a breaking news story last August of a proposed room temperature ambient-pressure superconductor but key measurements failed to be replicated by other laboratories.

-

It was determined that LK-99 was a more mundane diamagnet in a low-strength magnetic field, and developed ferromagnetic properties in a higher magnetic field - it didn’t seem to be a superconductor after all.

Here’s how this current publication stacks up to the previous work on LK99.

Is it the same material? Maybe.

The publication today has a slightly different chemical formulation by the inclusion of Sulfur, whereas previously LK99 did not incorporate this - although the starting ingredients in producing LK99 did include sulfur, and so, sulfur contamination may have been present in the original LK99 sample, but if the original authors thought it wasn’t present, then higher purity replications would’ve missed the mark by cooking up the wrong material.

In other words, that this current material includes sulfur doesn’t rule out that the effect is from the same crystal structure as the original LK99 authors reported (the general name for these materials is ‘lead apatite crystal’ which you will see floating around, like tiny rocks are want to do).

For both the current paper and the original LK99 and its other attempted replications, getting a high purity of the right crystal has always been hard, because the ‘right spot’ for the copper atoms in the crystal is hard for them to reach naturally, i.e. the lowest energy configuration which is the most likely was not though to get the right material properties.

So, the materials produced are low purity, might contain small specks of ‘the right stuff’, and its not completely known which is the right composition or how it works. There have however been simulation studies that don’t rule out such a crystal structure has the right properties believed to explain superconductivity at higher than ultra-low temperatures.

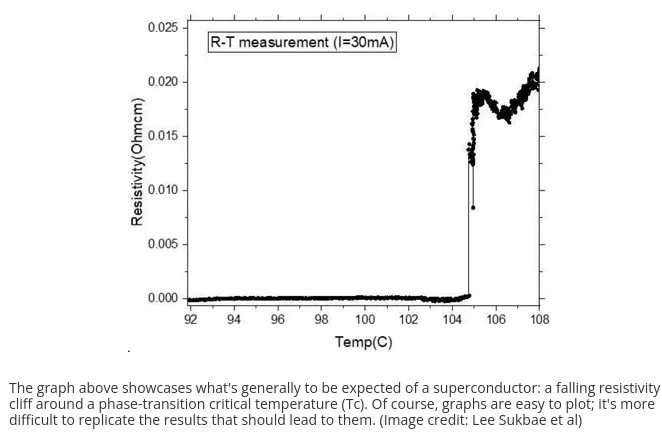

How did the researchers measure superconductivity?

A defining property of superconductors is their ability to perfectly expel an applied magnetic field, up to a limit. This is called the Meissner Effect. If the magnetic field is too strong, the material will fall out of superconducting state and back into a normal conducting state. The field strength at which this happens is called the Critical Field.

Developing superconductors that have a high critical field has been the material science breakthrough which enables the majority of current approaches nuclear fusion, so, it’s a big deal, although the critical field of this sample is fairly small - about 60x the strength of Earth’s field, or 0.2% that of an MRI.

The current publication measurement does the following:

- Cools the sample down to a low temperature

- Applies a DC magnetic field

- Measures the ability to expel this magnetic field, i.e. measures the Meissner effect

- Sweeps the field strength to find out the critical field

The susceptibility of a magnetic material is how easy it is to become magnetized in the same direction as an applied field. Since a superconductor expels magnetic fields, the susceptibility is negative.

The measurement technique they used is extremely sensitive as is based off a commercial device called an MPMS3 SQUID or Superconducting Quantum Interference Device. This is an extremely mature device built on 40 years of SQUID Magnetometry and can measure down to one part in 10e−8 in terms of sensitivity.

It works by measuring how the expelled magnetic field of a potential superconducting sample interacts with the current traveling in another superconductor circuit called a Josephson Junction (Josephson Junctions are also a fundamental building block of some designs of quantum computers).

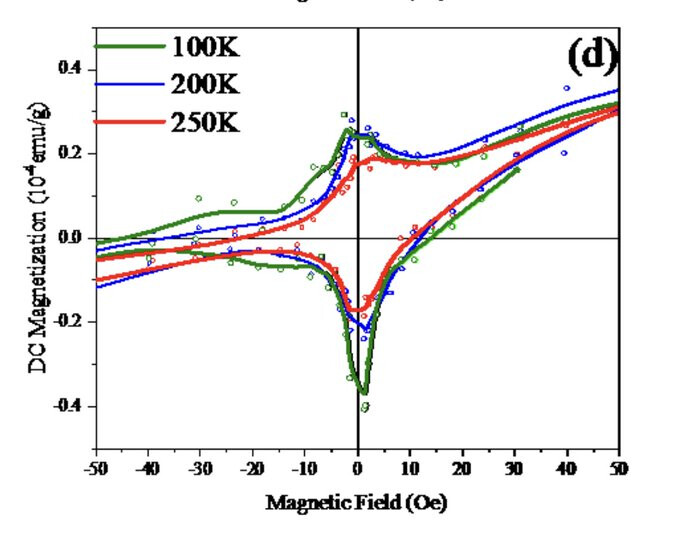

Here is probably the most important plot from the paper, showing the ‘Magnetization’ is negative for small field strengths, and this effect is slightly stronger at lower temperatures but still present up to 250K, or about −23C.

An important consideration here is that there is a ‘memory effect’ involved, where as you sweep the applied field to a low strength, and then back up to a higher strength, you don’t perfectly re-trace the result. This is called Hysteresis and is why there are two lines for a given temperature in the plot.

To understand this, there are actually two types of superconductors, Type-I and Type-II. Type-I will just perfectly expel a magnetic field until you hit the critical field, and then it all falls out of superconducting at once.

Type-II are different and more interesting. When you exceed the critical field strength, the magnetic field penetrates the superconducting material and forms a tiny current loop - the magnetic field aka flux is thought to be ‘pinned’ through the material, and around this ‘pinned flux’ circulates a tiny loop of current known as a vortex. Flux pinning is why Type-II superconductors levitate over a magnet, and the current vortices can influence the measured susceptibility of the sample and generate the hystersis effect, or, memory of past magnetic fields.

Type-I superconductors therefore always have a susceptibility of -1, while Type-II can have susceptibilities that are negative fractions, i.e. -0.3, as seen in the graph.

An oddity I will point out is their device, the MPMS3 SQUID Magnetometer, is also capable of performing a measurement technique called AC Susceptibility which is usually better at picking out superconducting from small grains in an impure sample, but the authors instead used DC Susceptibility. I’m not sure why they didn’t also run the AC Susceptibility test.

What’s the Net-Net?

The authors are careful to say this is a ‘Possible Meissner effect’ and that it is ‘near room temperature’ - which is wise. Last August, there was a lot of hype and a flurry of scientific interest, which didn’t pan out.

Scientists have to be very cautious to get things right and not over-state their claims, since their industry largely runs on reputation of credibility to be taken seriously by others in the scientific community.

It therefore makes sense that after last August, most people will treat this with a lot of caution, perhaps dismiss it entirely, or at least not engage with as much interest and fervor as last time.

The likeliest outcome here is that Lead Apatite Crystals just have some weird magnetic properties at low field strengths, and experience a transition in properties at near-room temperatures.

A much more exciting but lower-odds outcome is that Lead Apatite Crystals end up providing a fruitful line of research that develops room temperature superconductors, which means we don’t need to invade that planet from Avatar for unobtanium - we can produce it in bulk from some of the most common elements on Earth - Copper, Oxygen, Lead, and Sulfur.