A credit default swap (CDS) is a financial derivative contract in which the seller agrees to compensate the buyer, who pays a fixed premium in advance for the contract, if an underlying security (usually a debt instrument such as a fixed-rate, fixed-term bond) defaults (fails to pay interest, return principal at maturity, delays payments, or makes partial payments). Given the complexity of the instruments and possible events over the term of the contract, these contracts are usually very complex and may be customised by the buyer and seller, but the general concept is simple: it amounts to the buyer purchasing insurance from a third party against the risk of default by the issuer of the underlying security. As with any form of insurance, the buyer must also weigh the risk of the seller failing to pay when the risk becomes reality—this is referred to as “counterparty risk” and can be substantial when things get spicy in otherwise staid financial markets.

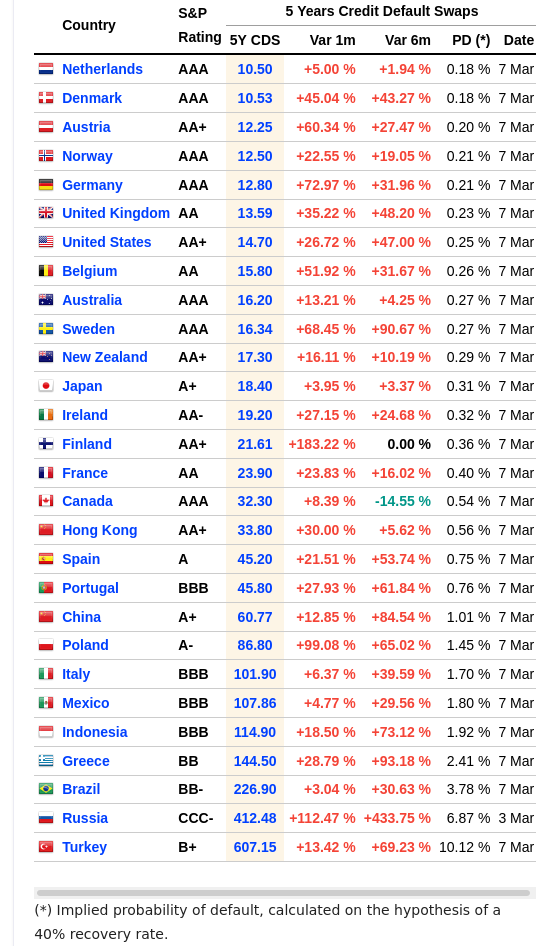

Although credit default swaps are complicated and can be customised, to allow comparison across issuers, securities, maturities, and time, they are often quoted in terms of basis points of premium on a contract with an underlying nominal value of US$ 10 million. For example, at this writing, a five year credit default swap on the sovereign debt of the United States is quoted at 14.70 basis points. Since a basis point is a “percent of a percent” that means the buyer pays 14.70\times\frac{1}{100}\times\frac{1}{100}=0.00147 of the amount insured for the contract. For the standard principal of US$ 10 million, this would be US$ 14,700 for the contract. (While credit default swaps are structured like insurance, you don’t need to own the underlying asset to buy a swap on it. A swap bought as a speculation on default of the asset is called a “naked swap”, and such swaps are estimated to account for around 80% of the total swap market.)

What’s interesting is comparing the swap rates, and implied risks, of the sovereign debt of various countries and the changes in these rates over time. U.S. Treasury debt is often said to be the safest investment in the world since it is denominated in the world’s reserve currency and the issuer has the ability to print new dollars at will to redeem its debt. And yet, given the political instability of that country and its history of brinksmanship and grandstanding over government shutdowns and increasing the statutory debt limit, credit default swaps on its bonds cost 40% more than those on the debt of the Netherlands, currently considered the least likely to default in the world. (If you really believe that climate change and rising oceans posed a real threat, why would a country more than one quarter of which is below sea level be the safest bond issuer in the world?)

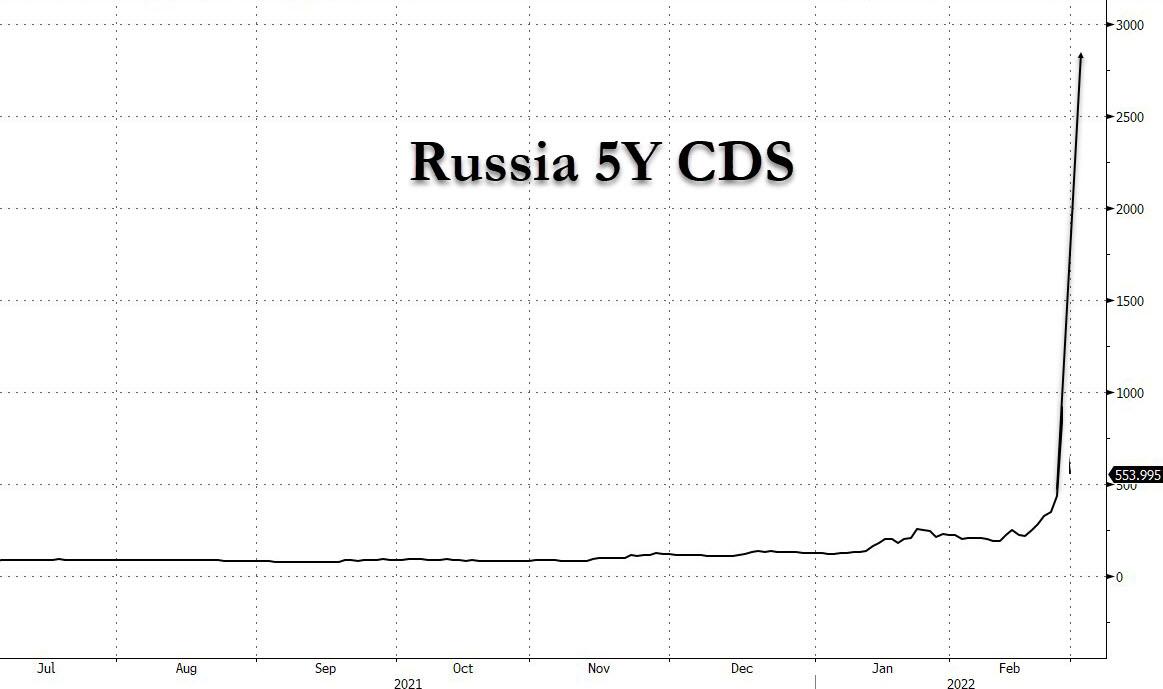

Anyway, comparing risk, as assessed by traders in the market with their (or their clients’) money on the line, is interesting, as is the rate of change in that perceived risk. Other than dramatic recent changes due to geopolitical events (see Germany, Poland, Finland, and Russia), what is also obvious is that recent instability in the foundations of the financial system (in particular, freezing the foreign exchange reserves of Russia by the central banks which held it on their behalf) has caused a world-wide increase in the perceived risk of sovereign defaults with only a few exceptions, notably Netherlands, Japan, and Canada.

The “PD” column in the table gives the estimated probability of default implied by the CDS rates according to a complex formula assuming creditors recover 40% from an eventual default. While the probability for the U.S. is just 0.25% and China is 1.01%, Russia’s default probability now stands at 6.87% (although it is unlikely many new CDS contracts are being issued on Russian debt, and the number comes from a thin and volatile market).

This is an interesting indicator to watch, as it indicates confidence in the foundations of the international financial system that underlies world trade.