A couple of weeks ago I would have vehemently disagreed with you, but after reading the article, How Not to Build a Country: Canada’s Late Soviet Pessimism, brought to our attention by @jdougan (thank you, @jdougan!), my view has changed 180° (I add this to a long list of beliefs I once held, but have changed over the past couple of years). I reproduce the relevant section for your convenience here (bold italics are mine):

Rent-seeking, Or How To Destroy The Wealth Of Nations

It was a meeting I had while working in mainland China that hammered home events in Canada. G——— had become a venture capitalist through pure grit. Like many foreign entrepreneurs in China, he had that weathered look about him and made it a matter of principle never to mince words. In middle age, he looked more like a rockstar than an investor—sporting a man-bun, a deep tan, and ripped jeans. He was always flanked by pretty assistants. You would never catch him in a suit, even at more formal events, among Chinese salarymen and party officials. “Welcome to Shanghai!” he exclaimed. “You made it to the center of the fucking universe, and if you want to survive here, you have to learn quickly and see the big picture.”

His advice for foreign entrepreneurs wasn’t some canned platitude about never giving up or how hard work paid off, but rather to read a specific book. “You want to understand what’s happening here? Go pick up Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.” The down-to-earth entrepreneurs think it’s a waste of time to read a tract three centuries past due, and the university-educated economist scoffs at reading quaint theory over the econometrics papers pumped out daily. But reading Smith to understand the crazy world of Chinese growth wasn’t about economic theory or its applications. It was about intuition.

That’s what innovators do. When the world around them goes crazy, they step back and look. When empty lots sell in the several millions of dollars, when shoddy rentals begin taking above 50% of the incomes of ordinary citizens, when 36,000 homes sit empty while offshore fortunes are laundered through them, it’s time to rely on intuition.

Smith, revered by deregulation proponents, understood that rent-seeking was a hindrance and imposition on productive activity. In his attempt to intuit the relationship between farmers and landowners in his 18th century Scotland, he devised the following relationship:

The rent of the land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give.

Smith uncovered the dynamic rent-seeking imposes on productive activity. Although many think of landlords as providing a service at a price determined by market forces, the reality is that they are barely providing a service at all, but merely extracting the largest possible share of tenant income by exploiting a geographic bottleneck. This is missed by the rhetoric surrounding the housing crisis. Landlordism in cities is (correctly) blamed for a worsening of income inequality. What’s ignored is the effect rent-seeking has on productive economic activity, and that the causes of income inequality lie in the crushing of productivity gains by such activity. Rent-seeking isn’t just a transfer of wealth from Millennial renters to Boomer landlords, but also a transfer of wealth from the productive segment of society to the unproductive.

There is a very simple way of looking at this transfer: wealth creation is making things.

When innovative companies begin making decent profits, landlords raise the rents to adjust for the new ability to pay. As a result, these additional wages are neither reinvested, nor reflected in the disposable income of employees. This is the dynamic behind the mystery of stagnant wages. When workers in a particularly well-paid sector begin pouring into a city, landlords likewise raise the rent to absorb these incomes. It isn’t gentrification, but absorption through monopoly power.

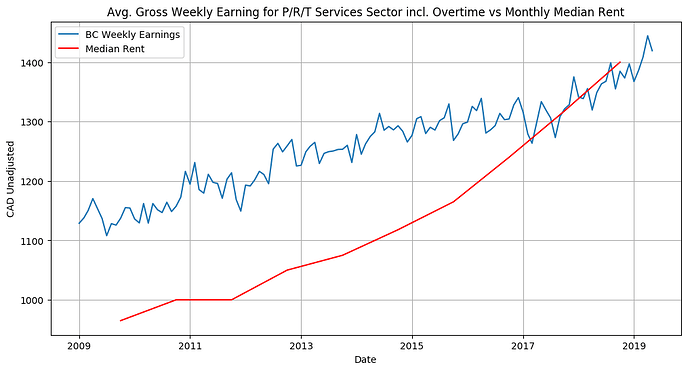

With this framework, we can begin to understand the effects that Canada’s out-of-control housing market has on innovation and productivity. Using data from StatsCanada and the CMHC, I’ve overlayed historical rents in Vancouver to average weekly earnings (pre-tax) of workers in British Columbia in the professional, scientific, and technical services sector, which gives us something like this:

Avetis Muradyan/StatsCan

Rent is rising with income, even slightly faster, absorbing much of the gains, as landlords are extracting an increasingly significant percentage of wealth generated by workers. As this trend drags into the new decade, it means being a productive worker pays increasingly less than speculating on the real estate market. It means that more and more people are pushing out of the productive sectors of the economy and into the unproductive, with the rentiers leveraging their assets and historically low interest rates to acquire even more rent-seeking opportunities. As the price of real estate inches ever upward, more and more people are left in the dust and at the mercy of the landlords.

It also means that real wealth creation is endangered. The sectors of the economy where goods and services are made and know-how is created shrink relative to our productive capacity as more capital, human and otherwise, becomes tied up in this real estate inflation. The rationale behind this asset inflation is the oft-repeated claim that the Canadian economy is undergoing profound technological change and that the influx of jobs in the transition will sustain demand for real estate in the decades to come. With the backing of major U.S. tech companies and urban transformation projects such as Sidewalk Toronto mushrooming in Canada’s top cities—-Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, Waterloo—the word in everyone’s mouth is Silicon Valley North.

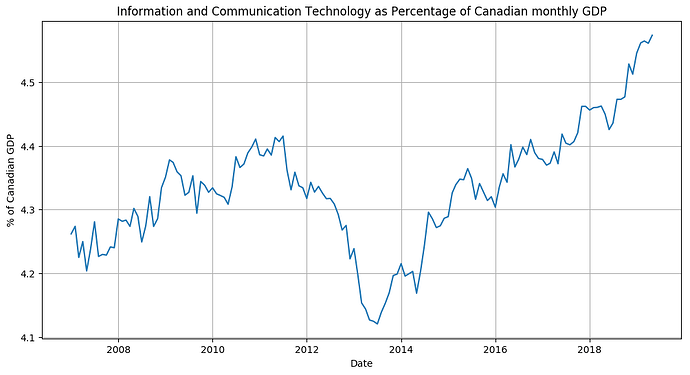

But a quick glance at sector data from StatsCanada dispels the idea of a Silicon Valley North:

Avetis Muradyan/StatsCan

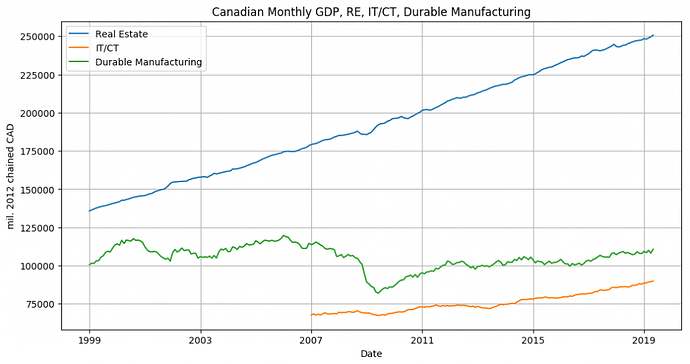

From 2009 to 2019, this supposedly prodigal sector has gone from occupying about 4.3% of production to about 4.6%. Hardly the much-touted silver bullet to Canada’s economic woes. The Canadian economy remains solidly stuck in a resource trap; the only sector actually delivering tangible growth is the one driven by asset inflation. To illustrate the point of Canadian real estate compared to Canadian innovation, the following chart is instructive:

Avetis Muradyan/StatsCan

How did real estate, the most low-tech asset class in existence, become more sought after than shares in the most bleeding-edge tech companies? Which came first? Did Canadian innovation fail because all the capital became tied up in real estate, or more uncomfortably, did real estate absorb all the capital because Canadian innovation could no longer deliver on its promises? Whatever the answer may be, it’s clear that Canadian innovation needs a new start as the threat of Brezhnevite failure looms on the horizon. A country that has a housing shortage when it is a net exporter of construction material, has nearly unlimited land, and has an oversupply of human capital, is stuck in the same rut as a country that has a shortage of toilet paper, just as it exports massive quantities of processed timber.